Soviet-style concrete monstrosity

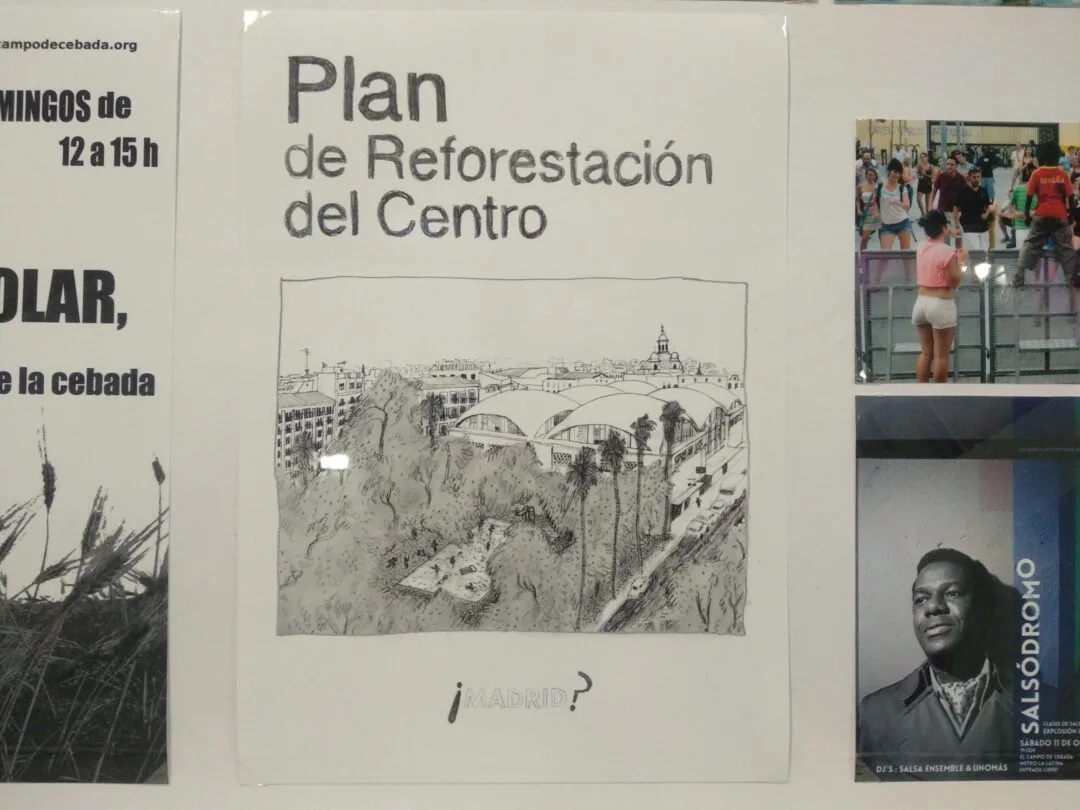

Earlier this month the new granite face of Plaza de la Cebada was unveiled to very little fanfare. While locals might have been excited to see a shiny new sports centre appear on what was once an empty lot, it’s hard to imagine anyone was particularly impressed by the blank stone surfaces of the adjacent plaza, especially seeing as plans made by the former mayor to plant trees had been scrapped by incumbent Almeida.

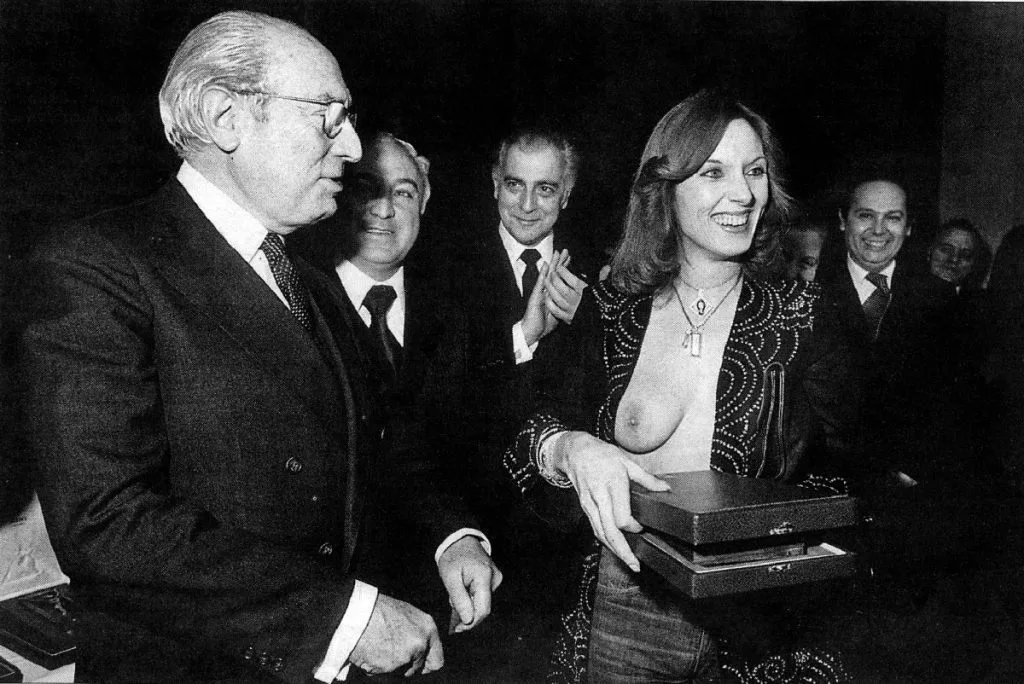

The new dour square makes a sharp contrast to what used to be a bustling neighbourhood space known as “El Campo de Cebada”: if you’ve lived in Madrid long enough, you might remember this plaza strung with fairy lights during the Fiestas de San Isidro or decorated with piñatas for Mexican-style festivities.

Now, the picnic tables, guerilla gardening and graffiti that made the space feel totally unique have gone forever, leaving the plaza a grey shadow of its former self. Feeling more than a little nostalgic for days gone by, it felt like it would be a good time to take a deeper dive back into the history of one of Madrid’s most iconic public spaces.

A bustling outdoor market

Cebada means barley and back in the 16th century Plaza de la Cebada was where farmers brought their grains, vegetables and salted pork to be sold. It was also where barley for the king’s cavalry would be acquired. Traders would enter the city via the nearby Puerta de Moros, or Gate of the Moors, a name that derived from the time when Madrid’s Islamic population lived in La Latina, previously known as the Morería.

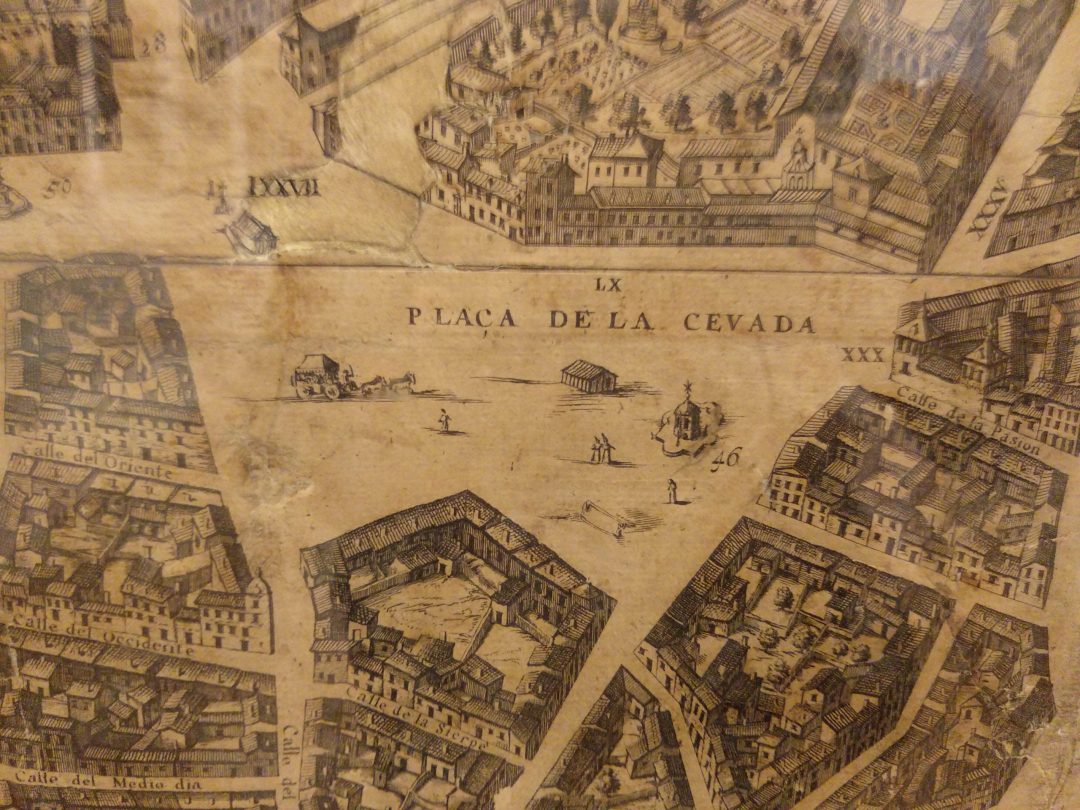

Though not a regular square shape, we can see from Pedro Teixeira’s 1656 map of Madrid, that Plaza de la Cebada used to be equally as big as Plaza Mayor. Not only that, but in the image below, we can also see the Fuente de la Abundancia, a fountain designed by Juan Gómez de Mora, an architect responsible for Plaza Mayor. To the left is a small humilladero, a devotional figure placed by the entrances to cities (in this case the Puerta de Moros), which visitors would bow or kneel before when passing in or out of town.

A darker history

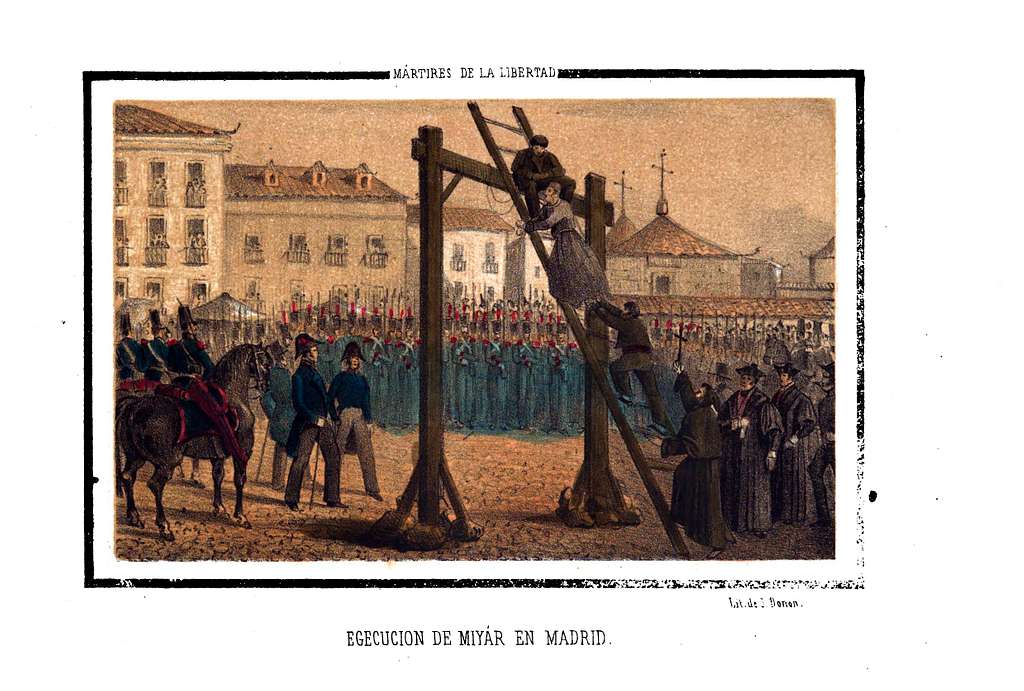

At the beginning of the 19th century, besides being the venue for a bustling outdoor market and local festivities, the plaza took on another darker role in the city’s public life when it became the venue for public executions previously held in the Plaza Mayor. Two major executions stand out from this period. In 1823, Rafael del Riego the Spanish general who fought the French to reinstate a corrupt king that then trampled on citizen’s rights was hung in the square for treason – his only crime was attempting to introduce a constitution. While in 1837, the popular rogue, Luis Candelas was killed by garote.

An execution taking place in Plaza de la Cebada in 1853

Madrid’s answer to Les Halles

Before the last public execution by garote was carried out in 1897, this bloody chapter in the history of the square was already over. With Madrid advancing into the modern age, its outdoor markets were now deemed unsanitary. The two churches that once stood on the square were demolished and a private company took on the project of building a gleaming two-story market of glass and iron in the plaza. This grand edifice inspired by Paris’ Les Halles was opened to the public in 1875.

Looking at pictures of the former Mercado de la Cebada, it’s hard not to feel sad that the entire thing was destroyed in the 1950s to make way for a new, less aesthetically pleasing market. In the naughties, just before the economic crash burst the construction bubble, a bid to regenerate the area saw the demolition of the sports centre next door to the market. The abandoned empty lot was a gift to locals who began to take charge of the space and transform it into the Campo de Cebada.

Construction frenzy

Now the concrete mixers and drills have started up again as Madrid tips forward into a post-pandemic construction frenzy that seems to be robbing many plazas of their personality. Plaza de la Cebada is not the only space to lose trees. According to El Confidencial, Plaza del Carmen and Puerta del Sol are among many other recently renovated treeless spaces. With temperatures rising and global warming accelerating, it’s hard to see the logic of these brutalist new designs.

Are you interested in the history of Madrid? Then why not take a unique walking tour with me, the author of this website?