The exhibition “Las Pequeñas Cosas“, on in the foyer of UNED until January 31 (but closed over the holiday period) is part of Mapas de Memoria, a project that couldn’t have been realised before the Ley de la Memoria Histórica was passed. During the transition to democracy, a political consensus to leave recriminations aside in order to move forward as a society, served to preserve the silence that Franco had imposed on the families of the victims of his regime. However, when Zapatero’s new law was passed in 2007, it allowed people to finally speak out about the suffering they had endured.

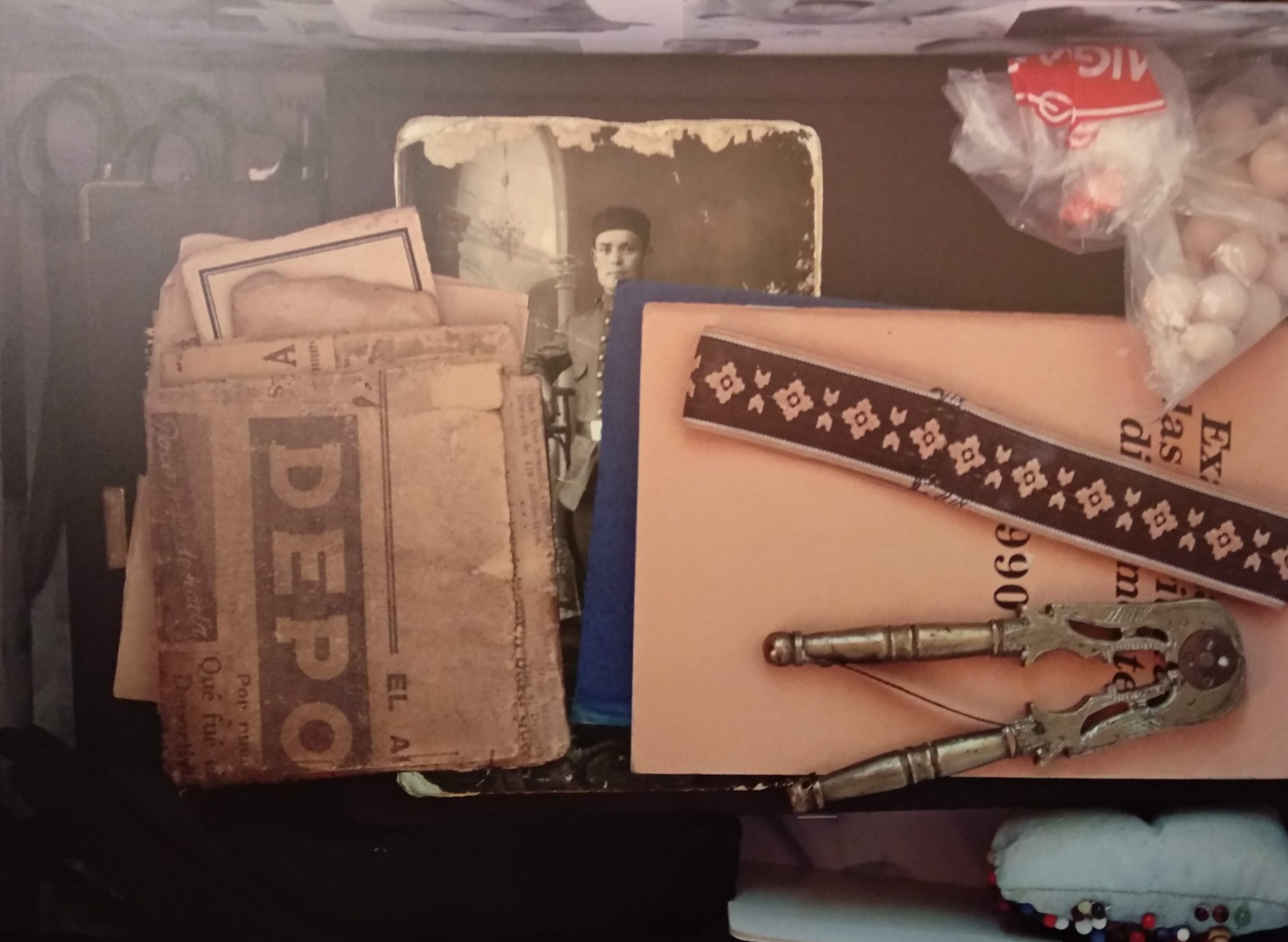

Getting people to talk has been a slow process, but thanks to the work of people like Jorge Moreno, one of the anthropologists working on the project – who literally went around knocking on doors for ten years – the stories of those who simply disappeared between 1936 and 1945 are finally being told. It’s a narrative that is difficult to put together because we don’t even know how many were killed: estimates vary between 100,000 and 200,000. Most of those put in front of firing squads simply vanished into unmarked graves. Their relatives were not permitted to mourn in public, nor were there any funerals, and neither could they speak out loud about the deceased. The only mementos they were left with had to be hidden away and taken out in secret.

Often they were given to wives who then passed them onto children when they died. With these children now in their 80s and 90s, it won’t be long before the stories attached to these objects vanish too.

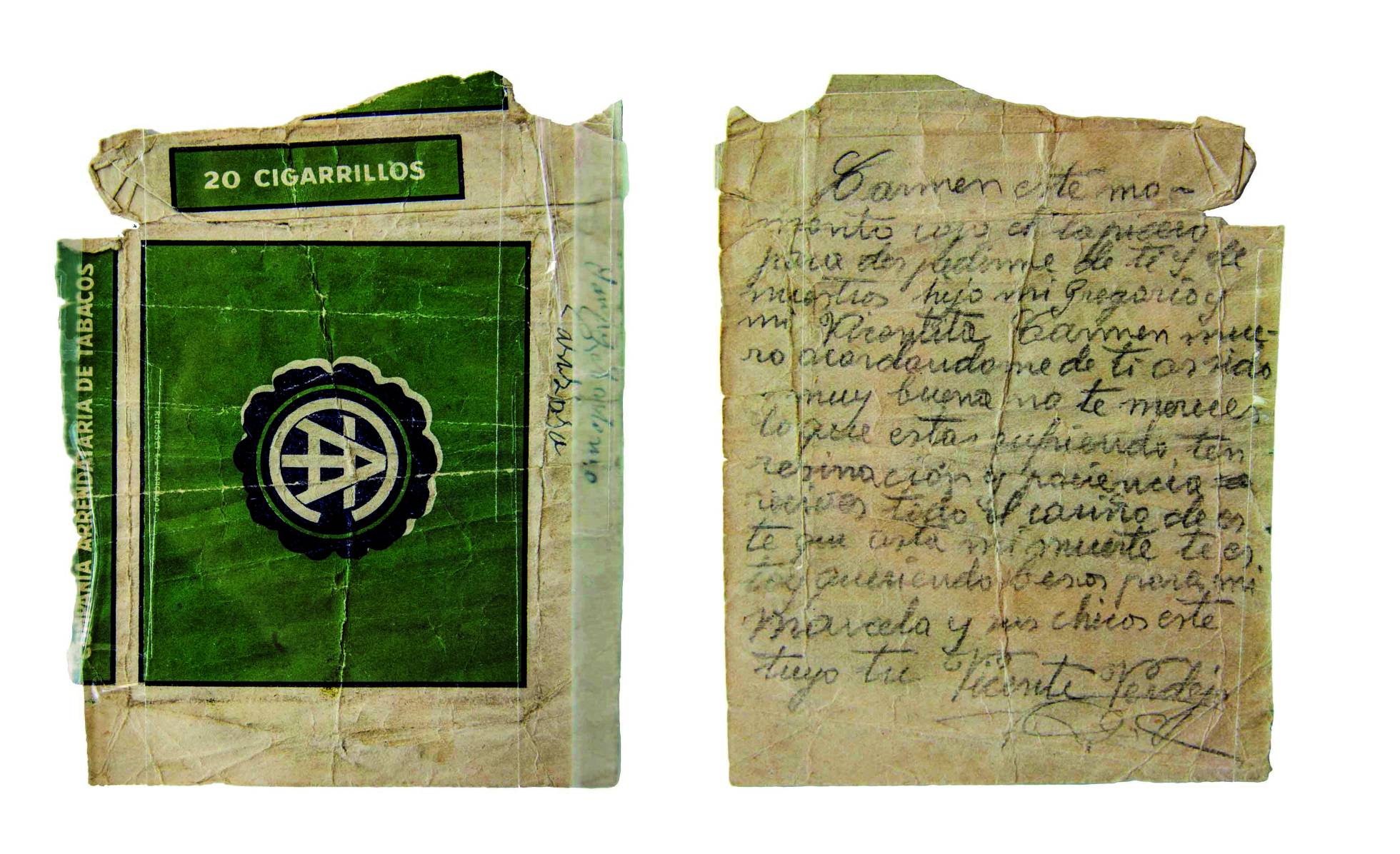

However, some of the objects on display need no explanation. Objects like a cigarette packet inscribed with the following note:

“Carmen, I’ve picked up this pencil stub to take my leave of you and our sons, my Gregorio and my Vincente. I die thinking of you. You have been very good and you don’t deserve what you’ve been suffering. Resign yourself and have patience. You have all my love up until I die. Kisses to Marcela and my sons. Yours always. Vincente Verdejo.” – Verdejo wrote these last words to his wife just before he was shot on the morning of 29 October 1940 at Valdepeñas prison.

Then there is the pouch containing stones stained with the blood of Ángel Ruiz, which was kept by the family in lieu of his remains. Or Fidela Vera Cardos’ collection of five faded photographs, the only reminder she had of her father and four uncles, all of whom were shot during the Civil War when she was just 11 years old.

Some of these relics show not just the suffering of those killed, but the trials of those left behind. A letter Anasatsio Godoy sent to his wife from prison instructs her to sell the wardrobe so she can survive and perhaps have enough money for paper and stamps to continue the correspondence.

In an introductory talk to the exhibition, Jorge Moreno explained how the grinding poverty and psychological toll was just too much for many widows, who often ended up taking their own lives. If they did make it through, they might be pressured into second marriages with men who supported the fascist regime.

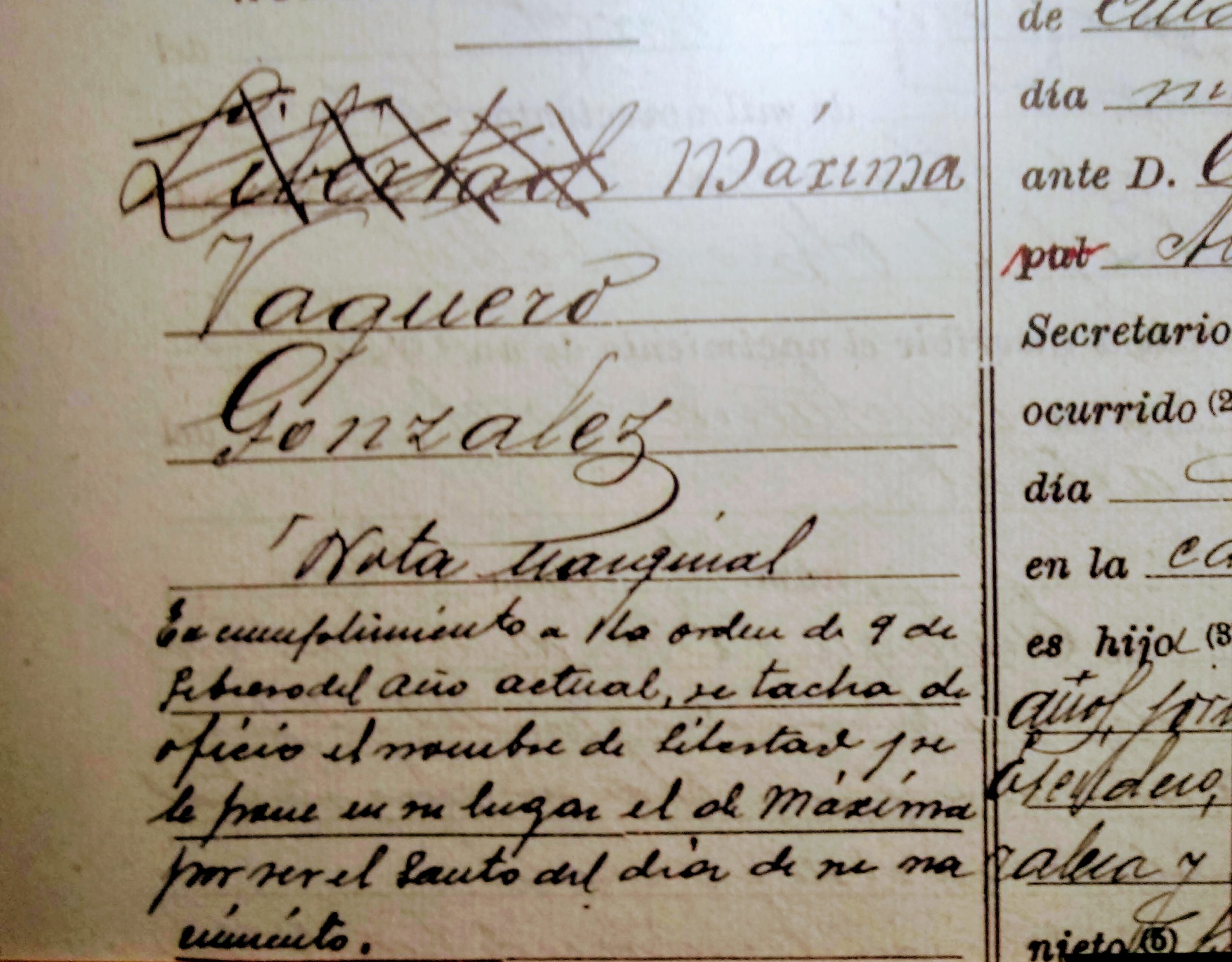

In addition to mementos, the exhibition contains archives from the time. These include the birth certificate of Libertad Vaquero, whose first name is crossed out and replaced with the name Máxima. Libertad, or liberty, was a popular name for girls during the Second Republic, but was later banned by Franco’s regime. An order from the Ministry of Justice on the 23 Feb 1939 gave parents 60 days to change names that were “exotic, extravagant, or carried certain associations”.

If you do make it to the exhibition (which reopens on January 7), you won’t find the objects themselves on display – these rightly remain with the families who’ve clung onto them for so long – instead you’ll be confronted with images of the items in question blown up to ten times their actual size. The accompanying information in the Spanish texts is rather harrowing, but it feels vital that these stories are now being told.

After the exhibition closes, it’s due to tour around Spain and the curators hope that visitors will be inspired to bring along similar objects of their own to add to the growing Mapas de Memoria archive.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to find out more about the history of Madrid, why not book yourself in for a unique walking tour of the city?

Pingback: When the Streets Had no Names - The Making of Madrid