Tucked away in the heart of the city, Cava Baja is renowned for its boutique hotels and posh restaurants. But 100 years ago the ambiance was very different. A busy hub for traffic going in and out of the city via the Puente de Segovia, the street was filled with stagecoaches travelling to and from Ávila, Segovia, Toledo and Salamanca. Passengers in these horse-drawn carriages were not members of the upper classes, but mainly peasants, farmers, and tinkers coming into Madrid to sell their wares. After the day’s business was done – often in the nearby Plaza de Cebada – most would spend the night at one of the cheap but cheerful inns along Cava Baja.

Three of these inns, or posadas as they’re known in Spanish, are still in business, but are now upmarket establishments, rather than basic flophouses. However, they all retain their original facades complete with large doorways leading to courtyards in which once stood carriages painted bright yellow and red in the colours of the Spanish flag.

The reason I know what colours the carriages were is because I’ve been reading Arturo Barea‘s splendid memoir “The Forging of a Rebel“. Barea was born in Madrid in 1897. The son of a laundrywoman who worked along the banks of the Manzanares, his portrait of the city at the turn of the previous century is at turns gut-wrenching and joyful. In one chapter, he describes Cava Baja is glorious detail:

“The centenarian inns multiply along it [Cava Baja] with their large wooden beams, their huge patios for carriages and their stalls for mules – all full of manure, flowerpots and brainless chickens – with their wooden staircases, polished by the passing hands of ten generations, with their little taverns next to the entrances, where wine is drunk straight from tripe skins.“

As a young city boy, Barea was particularly fascinated by the people who worked the land: “The customers are country people… girls – burned from the sun of ages – in their glad rags of luridly-coloured silk, and men in corduroy trousers that creak as they walk.“

Often the price of wheat and wine being brought into the city would be decided here and deals done on the spot. Afterwards the peasants and farmers would go shopping along the street before heading back home. Barea goes on to explain that Cava Baja was a world unto itself containing everything a person could need: a forge, a cooper, a sweet shop, a tinker selling framed pictures of saints and landscapes, a pottery, stables, a haberdashers, and even a furrier.

However, when it came time to leave, the journey out of Madrid down the Calle de Segovia could be less than pleasant, especially in summer when the temperatures soared. The carriage he travelled in as a boy was packed and unbearably hot:

“We go down Calle de Segovia, the carriage screeching: the slope is so bumpy that the brakes tighten until the wheels groan, and even so, the carriage is thrown against the mules. On occasion it has overturned in the middle of the street making the rest of the journey impossible. At the bottom we cross the Puente de Segovia and start to climb the road to Extremadura, which is also very steep.

“After the Puente de Segovia, Madrid ends and the countryside begins. Well, I say countryside, but there is nothing but some small dusty trees without leaves, fields of yellow grass scorched by fire and a few sheet-metal shacks owned by people in the rag trade… The road is full of dust and potholes that jolt the carriage so that the dust enters through the windows forming a cloud inside. The grit grinds against your teeth if you move them. But the sun is full and the windows cannot be closed, because then we would suffocate. One of the women has already gotten dizzy and has risen from her seat to stick her head out the window to be sick. When she does not vomit, her head dances in the window as if it were a puppet’s. By the time we arrive, she will have thrown her guts up, because it’s not yet been 20 minutes since we left Madrid and we still have more than four hours journey to go.” – And there I was thinking the coach journey to Granada was hellish!

When Barea travelled by stagecoach from Cava Baja, trains were already running for the rich, however, even after mass-produced automobiles started to appear, it continued to serve as a transport hub for the new buses. Of course, these days, it has long since lost that function. Now, it is very smart indeed, but as I mentioned earlier, you can still visit some of its posadas, so here’s the lowdown on them:

Posada de la Villa

Posadas first appeared in Madrid after Philip II made the city Spain’s capital and had its medieval walls demolished and new ones built. Under the southern edge of this wall were caves, aka cavas, (rumoured to have been mines dating from the Arab occupation of Madrid) in which thieves used to hide. This became the most dangerous area of the city, so the cavas were filled in. Later, in 1642, the Posada de la Villa was built on top to house members of the court. Now, it’s a swank restaurant in which celebs such as Bruce Springsteen have been known to dine.

Posada del Dragón

Posada del Dragón is named after a carving of a dragon that used to be above the Puerta de Cerrada (though other sources say it was above the Puerta de Moros). Founded in 1868, this posada originally provided lodgings to merchants and immigrants arriving in the city. In the 1980s sections of the city’s medieval Christian wall were found in the posada’s foundations and visitors can ask to take a peek at them.

Posada del León del Oro

Founded in the 19th century, Posada del León del Oro was also built on top of the 12th century city wall and visitors can view its remains through a glass floor in the restaurant. The golden lion in the inn’s name is a reference to the heraldry of Castile y Leon, which Madrid became a part of when Alfonso VI took the city in 1083.

Posada del Peine

Okay, so this posada is not located on Cava Baja, but instead, a few streets away in the Calle de Postas. Like the Posada de la Villa, it was originally designed to house members of the court when it was founded in 1610. While the Posada de la Villa gradually went downmarket, the Posada del Peine, tried to maintain a certain respectability, evinced by the addition of a comb (peine) to its rooms’ otherwise basic furnishings. The fact that this comb was chained to the sinks, perhaps undermined these pretensions to respectability!

British writer and adventuress, Edith A Browne recounts staying the night here for the very reasonable price of 1.5 pesetas (15 pence) in 1909. While she was horrified by the “ragamuffin” clientele, who had poured into the city for a fiesta, she was very impressed with the cleanliness and comfort of her lodgings. With 150 rooms, it’s the largest of the city’s posadas and certainly the most beautiful due to a loving restoration done in 2002.

If you are venturing into Madrid and would like to know a little bit about the history of the city, how about booking yourself in for a tour with me, the writer of The Making of Madrid?

Postscript: To write this piece, I’m indebted to a wonderful post in Urban Idade, which really helped give me a grounding in the subject. I highly recommend checking out this blog if you speak Spanish!

Wonderful article! I was under the impression that Cava Baja referred to the moat (foso) that the street followed along the medieval Christian wall rather than to any mines or caves ( cf, https://elrincondemayrit.blogspot.com/2013/08/por-que-se-llaman-cava-alta-y-cava-baja.html). Have you heard this?

Hi Larry. I did not hear that, but it’s highly likely. It can be hard to pin down the history of the medieval wall as Philip II had it demolished. I would give credence to the story that there were caves there as they were filled in in Philip’s time and record was keeping much better then. However, these caves may well have been covered over moats. The story about the mines is not certain at all and other people say the caves were escape tunnels under the wall for the Moors fleeing the city under a Christian invasion. I didn’t buy the escape tunnel story though as it doesn’t really make sense when you consider the timeline – the wall wasn’t there when Alfonso VI invaded and he was the one who ordered it constructed!

Hi Felicity, I’ve been trying to figure out the patterns of all the walls of Madrid. From what I’ve learned, the Visigoths may have built a wall around their village in the 7th or 8th century, then when the Moors invaded in 711, Mohammed I built the Alcázar and apparently expanded the existing wall a couple of times in the vicinity of what is now the crypt of the cathedral and as far as the Plaza de la Villa, and included the Puerta de la Vega. The wall remnant in the Emir Mohamed Park facing the Almudena is part of the Arabic wall. After Alfonso VI captured Madrid in 1085 (or 1083), the Christians expanded the existing walled area, building the “Medieval” wall, which is the one that passed the Plaza de la Cebada and followed the calle de la Cava Baja and the calle de la Escalinata, where they have found two more remnants of the ancient walls. Felipe’s wall followed the outer ring shown in the street patterns on the 1656 Teixeira map along the calle de San Pedro and through the Puerta de Toledo, then up through the Plaza Mayor. I will email you a portion of the Teixeira map with color-coded outline of the walls as best I can figure them out (and plotted on a modern aerial view of Madrid). I put this together for a memoir I preparing called Window on Madrid and Other Adventures.

Larry

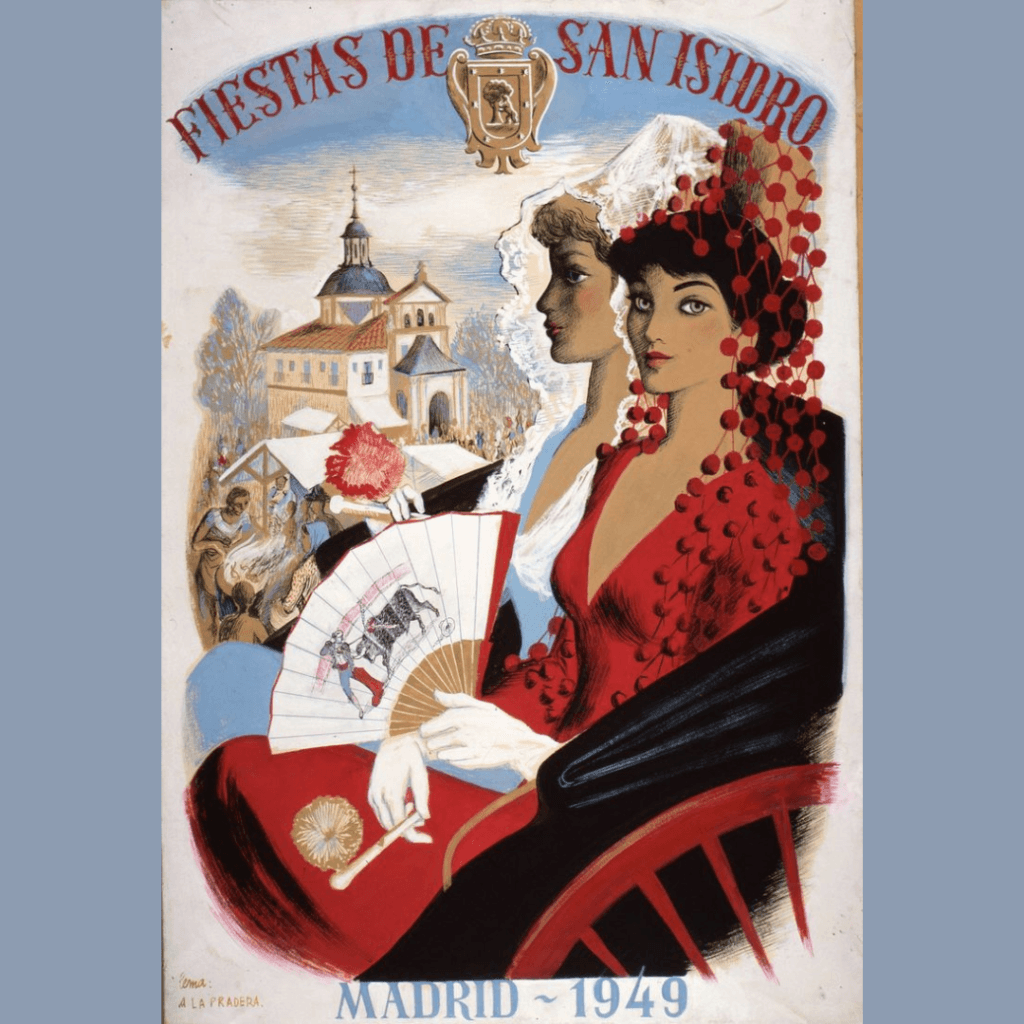

Thanks Larry. This is fascinating. If you do find yourself in Madrid again, pop into the Museo de San Isidro where they’ve recently built an installation with model and video about the evolution of Madrid’s walls. I did not know about the Visigoth wall though, nor that the Arabic wall was modified. You’ve certainly done your homework!

Did you know that you can also see a section of the Medieval Christian wall on Calle del Almendro? Great because it gives you an idea of just how flipping huge it was! I shall certainly be sharing your map (with credit of course) on my Facebook and Instagram accounts and hopefully use it in a post in future. Good luck with the memoir and let us know when it comes out.

Pingback: A brief crawl around Madrid's most historic bars - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: A Romantic Weekend in Madrid - The Making of Madrid