The murder of a 15-year-old boy earlier this year might have left many wondering if Madrid was a safe city to visit. This machete attack was particularly shocking as it took place outside a nightclub on Calle de Atocha right in the centre of Madrid. Reported widely in the English language press, the incident led to a mild case of media hysteria over the rise of gangs in Spain’s capital and provoked a police crackdown. But while this quelled outbreaks in central Madrid, fights continue to break out in poorer districts. Just last month, for instance, a teenager was taken to hospital with serious knife wounds while 20 others were arrested in a street fight in Usera.

Living in the eye of the storm

Usera is considered one of the worst neighbourhoods for gang violence. It’s also where I live. The same week I moved into our apartment in Almendrales, a man was shot dead just around the corner. A couple of years later, my husband witnessed a machete fight on the main road right outside our house. Later, in July 2017, another machete fight broke out in the square just outside our front door leaving two injured, this one making the nightly news. And these are just the incidents that have happened right on my doorstep. I’ve long since stopped counting the ones a few streets away.

You might think that with all this violence breaking out around me, I’d be worried. You’d be wrong. While I’ve witnessed several standoffs between young men who appear to be members of gangs, I’ve never once felt threatened myself. In fact, I’d say I feel far more secure walking home late at night in Usera than in London where alcohol-related violence is far more prevalent and drunken men appear to enjoy intimidating lone women. My point is that bystanders to the battle between gangs in Madrid are by and large completely invisible. It’s the vulnerable young men and women caught up in the drama that have the most to lose.

The underlying causes

Outlying districts such as Carabanchel, Vallecas and Usera seem to be bearing the brunt of this wave of violence. No coincidence that these are some of the most deprived areas in the city. The situation at home for many kids is extremely unstable meaning that they wind up on the streets where they are recruited to join gangs such as DDP (Dominicans Don’t Play) and the Trinitarios. Both Latino gangs were originally formed in New York and both are famed for using machetes to settle scores. Turf wars over territory are the main causes of violence. If a teen is recruited they will likely wind up getting involved in fights that result in injuries and occasionally, fatalities.

What these kids desperately need is a place to go. Initiatives like Guantes Manchados, a boxing gym in Usera run by volunteers are doing their best, but local facilities are underfunded and with little else to do, many are prey to recruiters. The police aren’t helping. During the crackdown, our square was regularly visited by officers carrying out nightly patrols that seemed to focus on harassing teens hanging out in the square rather than forging relationships. In my opinion, their overbearing stance did more harm than good, antagonizing the adolescents and making them more likely to seek out safety in numbers.

Plus ça change

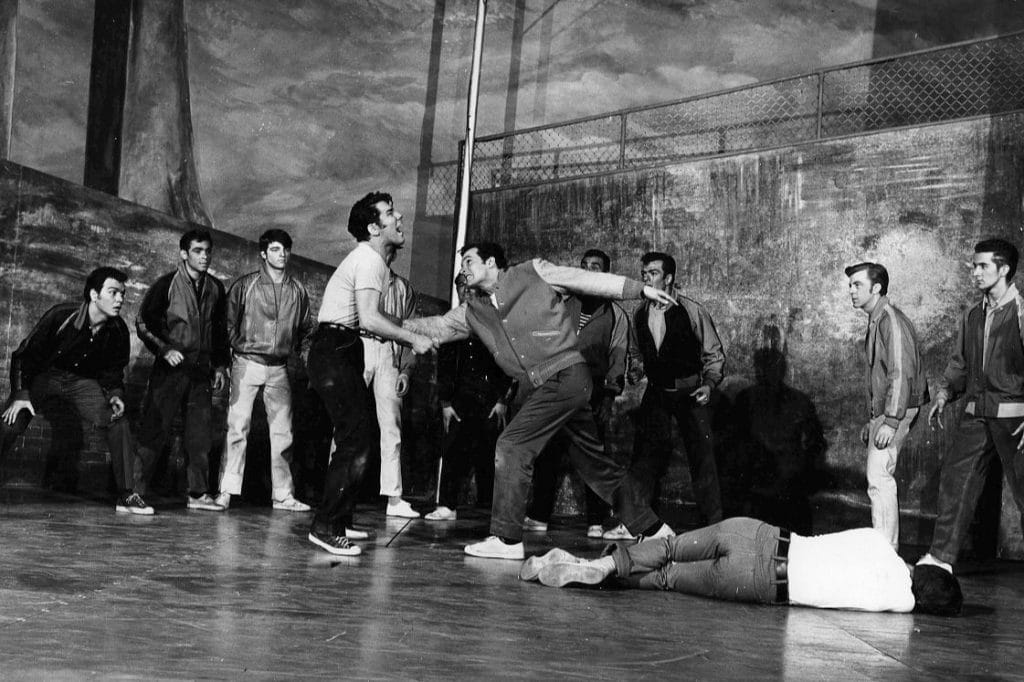

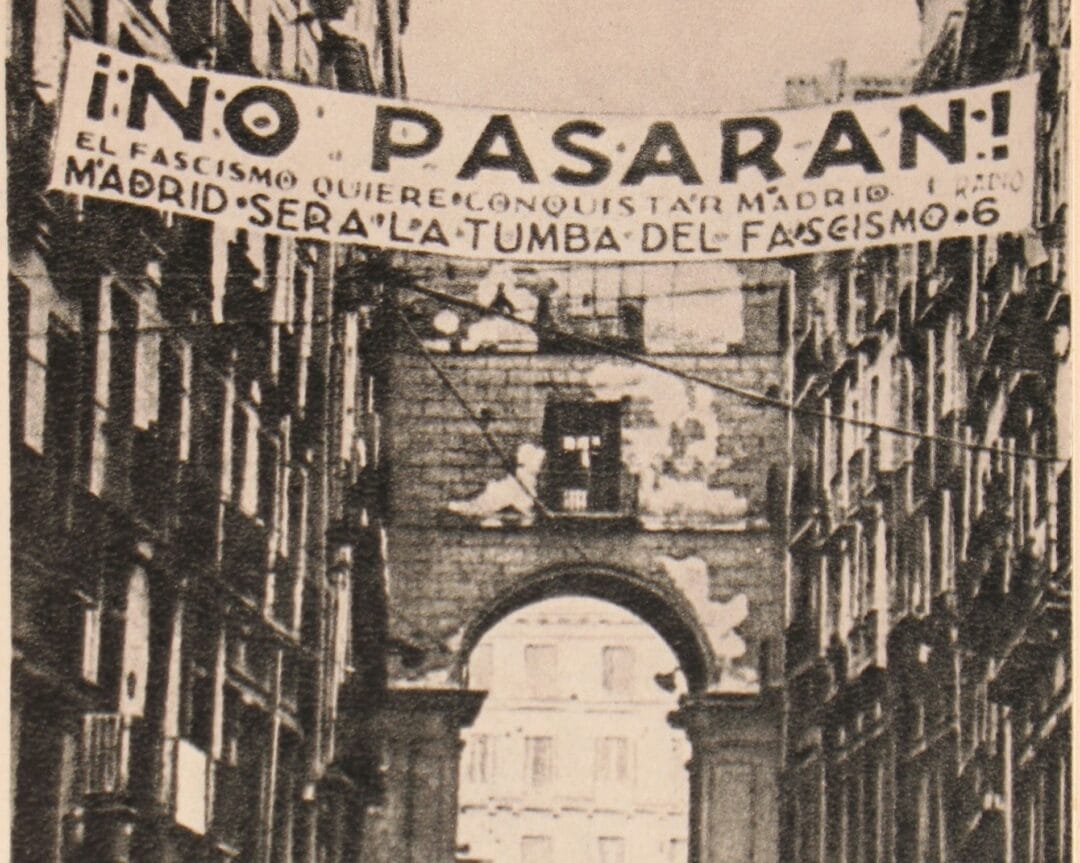

The gangs are nothing new. Usera and Vallecas have been fertile recruitment grounds ever since the 1960s. Both districts began life as shanty towns when the devastation following the Civil War forced many to move from rural areas to cities. While housing estates eventually went up in the late fifties and sixties, livelihoods were still precarious. With few jobs available to them, young men in deprived suburbs started to form gangs right around the time that West Side Story hit Spanish cinemas. Identifying with the rockers onscreen, they sported slicked-back hair, black jeans and leather jackets.

One of the most fearsome of these gangs was the Ojos Negros, the Black Eyes, named after their leader’s terrifying dead stare. Because he looked like an Indian, Ángel Luis’s nickname was Cherokee and, according to “All the Hate I Had Inside“, a book by Servando Rocha from La Felguera press, Ángel even got parts as an extra in spaghetti Westerns due to this resemblance. The gang made their money by robbing chemists or billiard halls, stealing cars, snatching purses or demanding protection money from local discos. Turf wars between rival gangs, such as the Vikings and the Pepsi Colas were frequent and many carried chains, knives and razor blades in case of a rumble.

Local hero

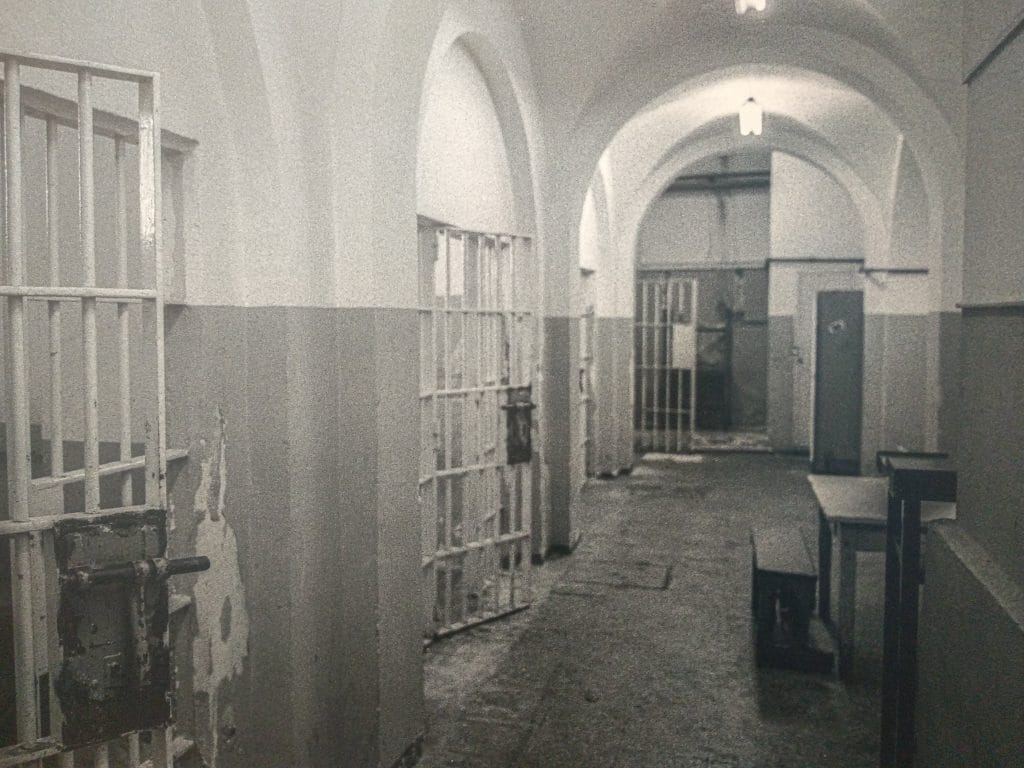

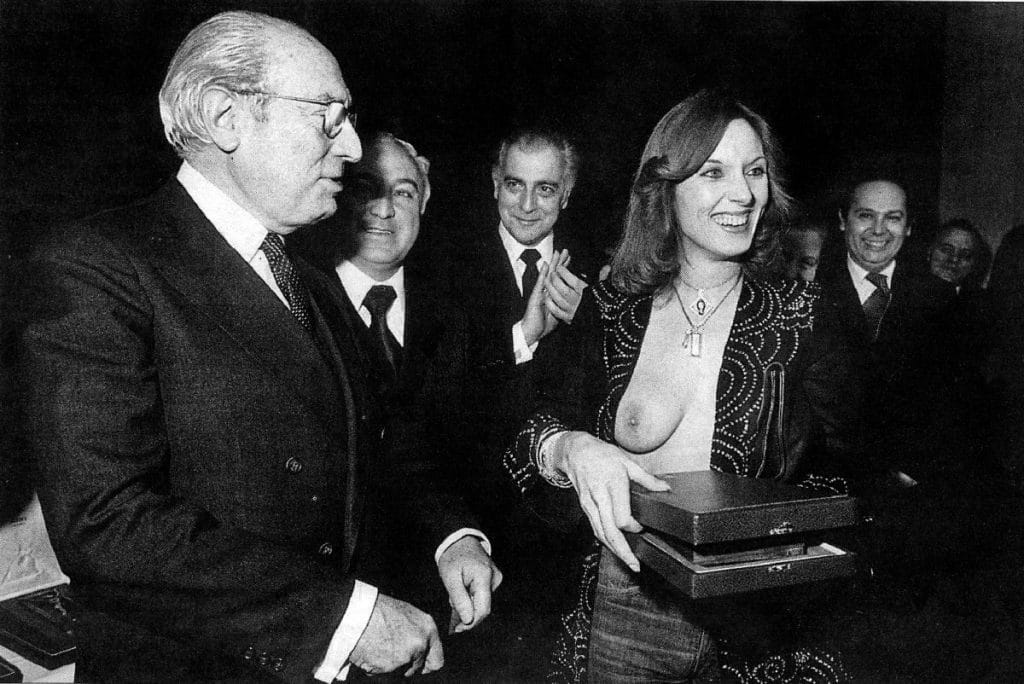

Ángel’s lieutenant later rose to become one of Spain’s most famous ever boxers. José Luis Pacheco, better known as Dum Dum Pacheco was a sensation in the 1970s. While in the gang, he was caught robbing a pharmacy and sent to jail. An extremely unstable life ensued and while he rose to become Europe’s welterweight champion, problems with gambling and alcohol dogged him. He’s now lost any winnings he earned and has returned to a humble life in Usera – I believe he lives just up the road from my house.

Gangs of yore

Back in the 18th century, before the neighbourhoods of Usera and Vallecas were created, Malasaña (then known as Maravillas), Chueca (then Barquillo) and Lavapiés were the capital’s main working-class barrios. Each had its own tribe. Malasaña had the majos that Goya loved to paint so much and Chueca the chisperos, so called because they were mostly smiths by profession and worked with sparks: chispas in Spanish. While there was no love lost between the majos and chisperos of Madrid Alta (upper Madrid), according to Somos Malasaña, they would call a truce and unite when facing off against the manolos of Madrid Bajo (lower Madrid).

Crime in Madrid

Despite the gang wars, modern Madrid is a much safer city than it was back in the 18th century when Charles III had to ban long cloaks to stop surprise muggings in the street, or even in the 17th century when swordfights were a common occurrence. That’s not to say there aren’t any dangers at all. Madrid is a relatively safe city, but it’s a city still reeling from the blows of the 2008 economic crisis and the pandemic. A city suffering the effects of yet another unfolding financial catastrophe. No surprise then that pickpocketing is rife, particularly on the metro and in crowded spots like Sol and the Rastro. Be assured that if you do get robbed, it’s highly unlikely someone will use a knife on you. So keep your wallet tucked away out of reach, hold tightly onto your belongings and be aware of your surroundings.

If you’re interested in the history of Madrid and are visiting or live in the city, you might want to book yourself in for one of my guided tours. I am also available for customized private tours of the city.

Pingback: Five scams to avoid in Madrid - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Six scams to avoid in Madrid - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Is Madrid Safe? A Tale of Three Cities - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: A History of Violence in Madrid - The Making of Madrid