Caught on canvas or let off the hook?

Portraiture is a tricky business. An artist has to balance capturing the true likeness of the subject with flattering their ego. If said subject is a nasty piece of work, the job just gets even trickier. This post features three portraits of Spain’s most notoriously nefarious rogues, all brilliantly executed by artists at the top of their game. The paintings are on permanent display in the Prado, so if you’ve got a free afternoon, I urge you to check out this rogues’ gallery at close quarters. And when you’re done. Let me know what you think. Did Rubens let slip that he thought the Duke of Lerma was a complete and utter bounder? Did Velazquez betray King Philip IV’s sensuous nature? And last, but not least, did Goya reveal the brutality behind the pomp?

The Duke of Lerma

When Rubens came to Spain as part of a diplomatic mission, he was told there was only one person worth painting and this was not King Philip III himself but his valido The Duke of Lerma. Ruling Spain for a king who preferred to while away his time hunting and gambling, the duke carried out a huge property scam that defrauded the crown out of a fortune. When this portrait was painted in 1603, this scam was in full swing with money from the royal coffers pouring into Lerma’s pockets.

Natural then that the visiting Rubens was told not to bother painting the king’s portrait, but to pour his efforts into this stunning equestrian painting of his “loyal” valido. While Rubens was proud enough of the piece to sign the portrait, he took a dim view of the duke himself, later writing: “…it is difficult to conduct affairs in a country where a single man has the power and where the King is only a figurehead… This is a state of affairs which cannot long endure. May it please the Lord to change it for the better.”

While the duke’s nefarious schemes did catch up with him, he was never prosecuted for his crimes having already convinced the pope to make him a cardinal. The majority of the blame was placed on the shoulders of his righthand man, Rodrigo Calderón de Aranda, who was executed in Plaza Mayor in 1621.

Philip IV

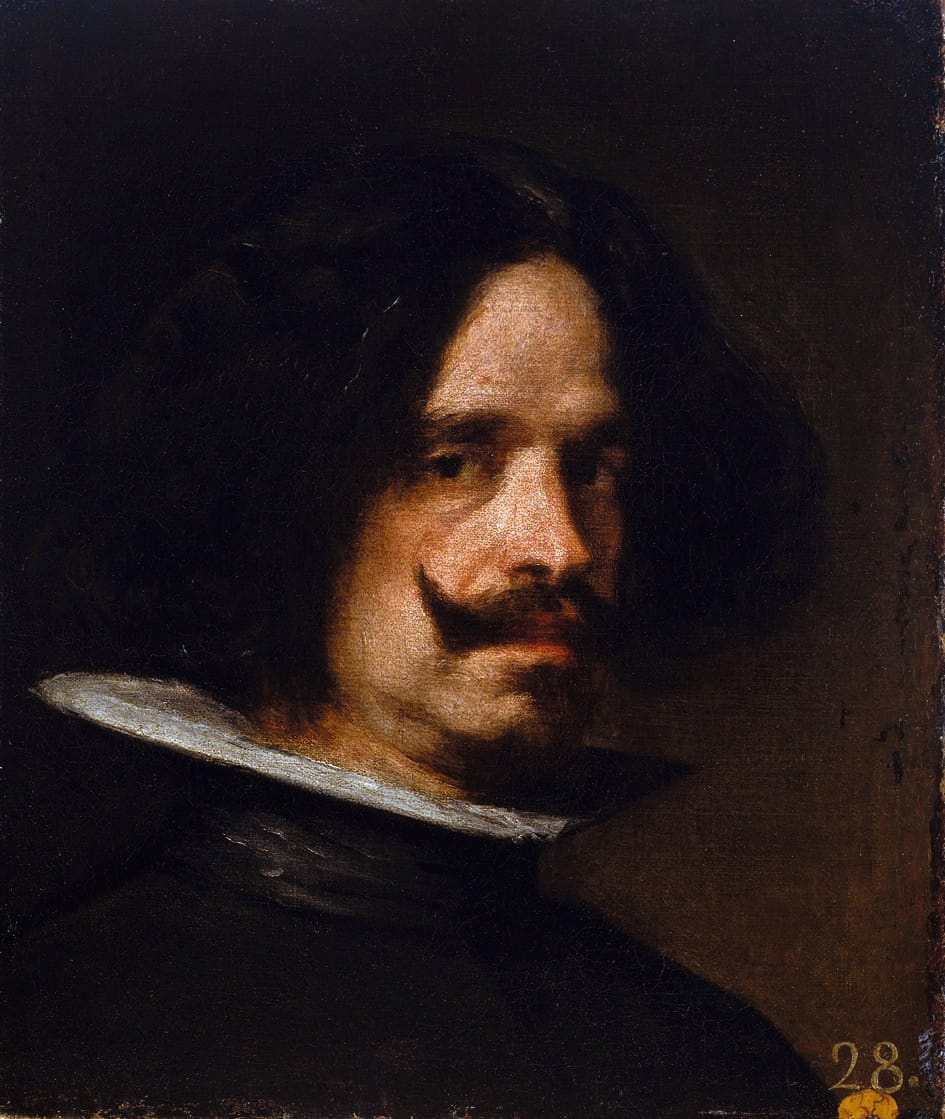

When Philip III died, the reputation of the bankrupt monarchy was in tatters. His heir Philip IV would have to make up for his father’s sins to win the public back over. However, the young king was far more interested in the theatre and art than in statesmanship. Like his father, he appointed a valido to run the enormous empire he’d inherited. Fortunately, the Count-Duke of Olivares was a much more trustworthy figure than his predecessor. Olivares believed that if he could make the king appear to be as devoutly Catholic and earnest as his grandfather, Philip II, he might repair some of the damage done by his father, Philip III.

To keep the king happy away from the public eye, he built a pleasure palace in Retiro where Philip could watch plays to his heart’s content. In exchange, Philip would not only dress in sober blacks like Philip II, but he would also discard the froufrou ruff of the aristocrat in favour of a new slimmed-down version. The idea was to show he wasn’t wasting cash on frivolous fashion choices.

In the portrait above, the king’s head sits atop a stiff plate-like collar. Examined closely, it looks like something worn by an alien ambassador. However, many people find that they tend to remember the king in a full ruff, their minds filling in this detail by conflating it with other royal portraits of the period.

The painter of this masterpiece was Velazquez. A close companion to the king, it’s often thought that this role prevented the artist from painting as much as he would have liked. The king, too, often roped into attending tediously long state functions, was duty-bound to spend time away from his own passions. Philip’s interest in the theatre was more than matched by his love of the ladies. A notorious sex addict, it’s estimated that he sired between 20-40 illegitimate children with various different women, in addition to his 13 legitimate offspring. One of the king’s favourite lovers was an actress called María Calderón. He was so fond of her that he dared to face public scandal by acknowledging her son, making sure John Joseph of Austria would have a brilliant career in the military.

King Ferdinand VII

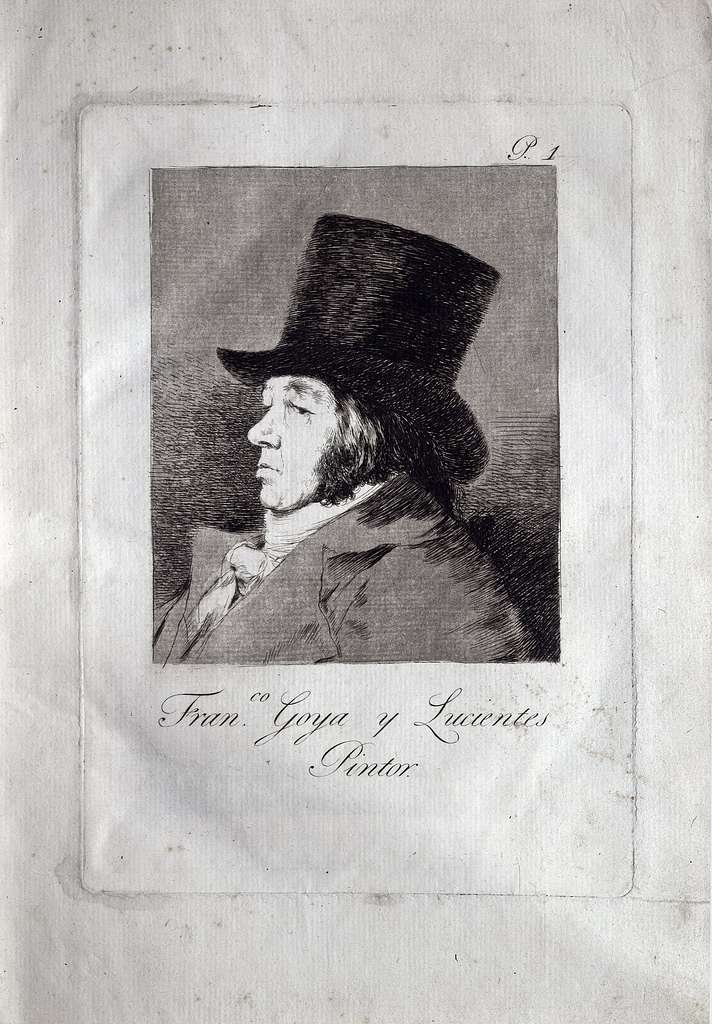

The third and final portrait in my rogues’ gallery is an 1814 portrait of King Ferdinand VII by Franciso de Goya. Painted shortly after Napoleon had been thrown out of Spain and the king restored to the throne, public support for the desired (el deseado) monarch was gradually draining away as citizens’ hearts filled with private anguish. Later that same year, Goya too must have experienced some difficult sensations as the “purification” process to rid Spain of collaborators under the French regime sent many into exile. As Goya had also been “first court painter” during the brief reign of Joseph Bonaparte, he had reason to be fearful.

Though later given first-class clearance in April 1815, his troubles weren’t over as an investigation by the recently restored Inquisition got underway. While he was acquitted on the charges of obscenity for paintings that included The Naked Maja, it’s thought that Goya, along with many liberals was thoroughly disillusioned with the new rey felon (criminal king).

In addition to reinstating the Inquisition, Ferdinand shut down the free press, forced many liberals into exile and tore up the Constitution of Cadiz. Knowing all this, it’s easy to read too much into this portrait. I myself feel that Ferdinand seems to be gripping his scepter with murderous intent, but it’s important to remember that Goya’s fate, of course, was hanging in the balance. So, he would have been careful not to offend his subject.

You decide

Painted against a gloomy background, Goya’s painting of Ferdinand VII refers back to those of his predecessor and master, Velazquez, who often used plain dark backgrounds to bring his subject into relief. There are other parallels in these portraits. We know that all three painters featured in this rogues’ gallery of Spanish rulers – Rubens, Velazquez and Goya – would have been aware of the personal failings of their subjects. But principles don’t pay the rent and the fees pocketed for these commissions would have been considerable. While this is, of course, subjective, there’s a certain smugness to the Duke of Lerma’s expression, a certain sensuality to Philip IV’s full lips and a certain brutality about Ferdinand VII’s pose that suggests all three took some risks while painting this rogues’ gallery of Spanish rulers.

If you’re interested in finding out more about the history of Madrid, I can be hired as a guide to the city. For more information click on the tours section of this website.

Books referred to: The Letters of Peter Paul Rubens, translated and edited by Ruth Saunders Maugurn / The Portraits of Goya by Xavier Bray.

Pingback: The Hapsburg Jaw - The Making of Madrid