It’s not easy piecing together a Jewish history of Madrid. While nearby Toledo has not one but two medieval synagogues, little hard physical evidence of Madrid’s Jewish population remains. This stands to reason as Toledo was, of course, a much larger and more important location in medieval Spain. But documents attest to the fact that Madrid did indeed have a Jewish community. And yet, archaeologists have had a hard time finding evidence to support this. The fact that they left little behind could be in part due to a grim chapter in Spanish history.

In 1391, an angry mob ran amok through the streets of Spain sacking Jewish houses and murdering Jews who refused to convert to Christianity. Starting out in Seville and moving on to Aragon and Castile, these attacks spread like wildfire across the country. Because nobody was held accountable by the authorities, disgruntled citizens in Madrid also felt emboldened to lash out. The national death toll was enormous, some putting it as high as 50,000. According to one account, many of the city’s Jewish population were murdered. We do know that by 1481, just before the Jews were ejected from the country altogether, Madrid only had around 200 Jews remaining. Many perhaps had sought refuge in the larger community in nearby Toledo after the massacre.

Lavapiés

The dearth of information on Madrid’s Jewish community left the door open for romantic writers in the late 19th century to invent an alternative Jewish history of Madrid that is often still mistaken for fact. Many Madrileños will tell you that Lavapiés was the Jewish quarter of the city. They’ll confidently state that Lavapiés means the washing of feet, and that this is a reference to the Jewish practice of feet washing before entering a synagogue. In this version of the Jewish history of Madrid, Lavapiés square was built on the ruins of a synagogue.

This story is, of course, piffle. The washing of feet before worship, while common in Islam, is not something demanded of Jewish worshipers. Furthermore, there is no archaeological nor documentary evidence to suggest a synagogue ever stood in Lavapiés square. While it’s certain the medieval city had a Jewish quarter, Lavapiés is way too far away from the protection of the old city walls to be realistically considered a candidate. If we are to attempt to reconstruct a Jewish history of Madrid, this isn’t the best place to start. And yet, a grain of truth can often be found in myth.

The Manolos

What’s far more likely is that Jewish conversos, that is converts to Christianity, did live in Lavapiés after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. Fearing the Spanish Inquisition, it would make sense that these conversos might prefer to live together rather than risk being denounced as heathens by jealous neighbours. This tribe of conversos came to be nicknamed Manolos, due to a supposed prevalence for the name Manolo amongst Jewish converts. The moniker derives from Emmanuel, an Old Testament name which also means “God is with us” in Hebrew. While I’m not so sure these converts would be keen to advertise their heritage, it does make sense that Manolo could have been used as a derogatory epitaph by other working-class tribes in Madrid.

Madrid’s actual Jewish quarter

Documents tell us that the Jewish quarter or judería was originally located right in the heart of the city where the museum of Almudena Cathedral now stands. Historically, this makes far more sense. They would have originally been installed there by Madrid’s Muslim rulers after the city was founded as a garrison town by Muhammad I of Cordoba back in the later half of the ninth century. Two small pieces of archaeological evidence back this theory up. On this site the following were found: a ceramic fragment depicting a menorah and a hole in the jamb of a door possibly used to attach a small box containing the mezuzah (a scroll with verses from the Torah).

Interestingly, this wasn’t such a bad place to be. While Jews were considered second class citizens in the kingdom of Al-Andalus, they were valued for the financial services they provided and for their skills as translators. Because of this, they were given quarter within the safety of the city walls with agricultural land close by – unlike the Christian population who lived rather exposed in farmland out in the area of La Latina. Though citizens of both faiths paid higher taxes than Muslims, they were allowed to practice their religions unmolested. For the Jews, who had been persecuted under Visigoth rule, this was a much preferable state of affairs.

From Muslim to Christian rule

Conditions for Jews and Christians in Al-Andalus took a dramatic turn for the worse in 1147 after the Almohad invasion from North Africa ushered in a new period of religious intolerance. Persecuted Jews then fled to the relative safety of Christian Spain. To cities like Madrid, which had already been conquered by Alfonso VI in 1083.

After Alfonso’s invasion, things went on as before. Lower class Muslims stayed behind and were moved to the less desirable area of La Latina, while the Jewish quarter remained where it had been, with Jews allowed to engage in the same kind of trades. However, from the 13th century onwards, intolerance towards Jews and Muslims began to sweep across Christian Europe. The Laterian Council of 1215 stipulated that both Jews and Muslims had to wear identifying garments. This clothing differed according to country. However, in Spain, for Jews, this consisted of a badge with a yellow circle drawn on it.

A growing threat

Over the course of the next few centuries, anti-Semitism waxed and waned with this rule being only intermittently enforced. However, once the massacre of 1391 took place, forced conversions, accusations of desecration of Christian symbols and violent attacks, were on a definite upward trajectory. By 1481, Madrid’s 200 remaining Jews were forced to move out to less desirable neighbourhoods outside the city walls around Sol and Puerta Cerrada.

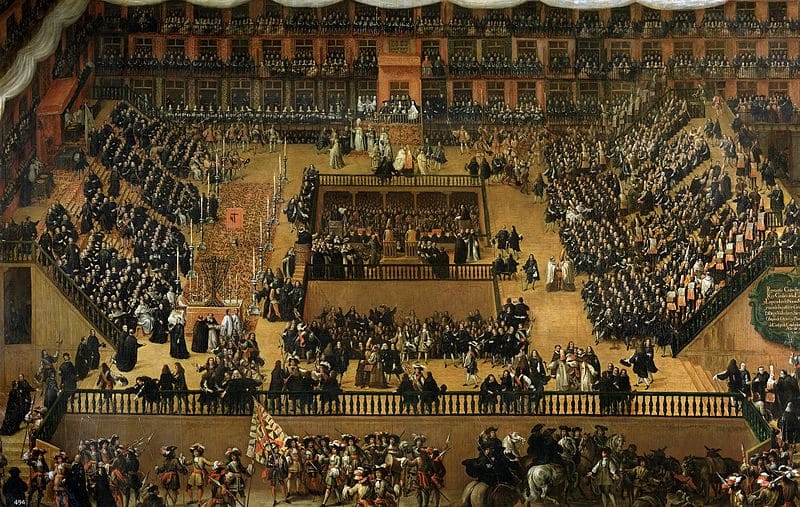

Their time in the city, of course, was running out. By 1492, the Reyes Catolicos had completed the Reconquista of Spain and ordered all Spanish Jews to either convert or leave the country. Those that remained faced constant scrutiny by the Inquisition standing trial in the notorious Auto de Fe. In 1642, for instance, 44 converso convicts were rounded up. Accused of whipping a statue of Jesus, most confessed, while seven were labelled unrepentant heretics and burned at the stake.

Making amends

Now, of course, Spain is trying to make amends for its brutal treatment of its Sephardi population, granting nationality to those with a connection to Spain back in 2015. However, processing these applications is taking a long time. The deadline was 30 September 2019, but everything has been slowed by Covid. While over 6,000 applications have been successful, there remain over 100,000 to be processed.

Still, Madrid does now boast the Centro-Sefarad-Israel, which aims to educate Spanish citizens about Jewish culture as well as an actual synagogue with a museum of Jewish history in Madrid attached.

If you’re interested in the medieval history of Madrid, I’d recommend coming on either my Madrid, the Early Years tour or my Muslim Madrid tour. I run both occasionally on Meetup, but can be hired privately at your convenience.

Hi Felicity,

Love your articles. Think you should publish a book!! I’d certainly buy a copy. Hopefully will catch up again on one of your tours.

Thank you Carol! Yes, I would love to see you on a tour soon.

Pingback: Toledo's Jewish History - The Making of Madrid