From the street, Madrid’s only remaining pelota stadium doesn’t look like much. Painted a genteel cream and white and decorated with ornamental columns and balustrades, it blends nicely in with the very Parisian look of Madrid’s northern neighbourhoods. But behind its polite public façade, a fast and furious version of pelota called cesta punta, or jai ali (meaning ‘merry festival’ in Basque) was once played for high stakes. With heavy leather balls ricocheting off walls at speeds of around 200 kmph, just like in bullfighting, injuries were common and players had to be at the peak of physical fitness to wield the cesta, a wicker basket worn as a prosthetic extension of their own arms. So, it’s perhaps no surprise that the true brick face of the stadium, seen when you enter through a side entrance, looks exactly like the curved edge of a bullring.

Built in 1893 and designed by Spanish architect Joaquín Rucoba, Beti Jai was riding on the crest of a sporting craze that swept the capital. Between 1891 and 1894, four fronton (pelota courts) went up around the city. The trend had begun in San Sebastian, which in the latter half of the 19th century was a popular summer resort for wealthy Spaniards escaping Madrid’s blistering heat. The visitors, looking to spice up their summer holidays started attending local games of Basque pelota and found that they thoroughly enjoyed not only the sight of ripped Basque players whipping the ball around at top speeds, but also the thrill of betting on which teams or players would score the most points. When the queen regent, Maria Christina of Austria, developed a taste for the sport, the deal was sealed and pelota games started being held in Madrid.

In the late 19th century the game became so popular, not just in Spain, but also in France, that pelota players were some of the best paid sportsmen in the world with cesta punta even making an appearance in the 1900 Olympics. Its popularity began to even spread to the rest of the Spanish speaking world gaining fans in Mexico, the Philippines (where it was eventually banned because of its links with gambling) and Cuba. From Cuba, it was a hop skip and a jump to Florida, where it’s still played to this day, though interest has waned since the 90s. Back in Madrid however, pelota fared a lot worse. So many competing stadiums in a city of just 500,000 residents could not hope to fill their seats for the daily matches that were held. On top of that there simply weren’t enough professional players to meet demand and the quality of the game suffered.

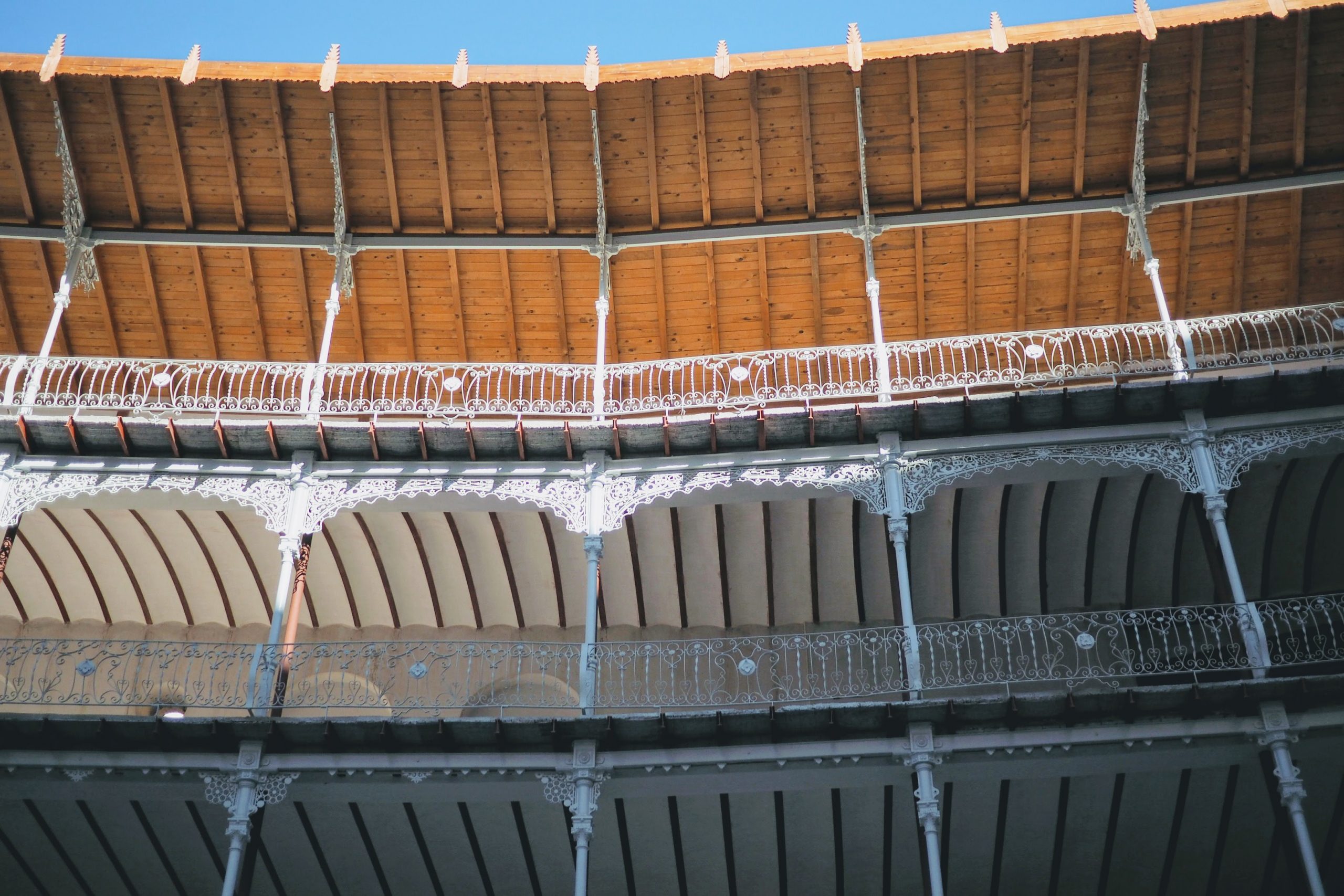

Though other events were held at the Beti Jai, it wasn’t enough to keep the stadium running and in 1919, the building was converted into a car factory. Over the subsequent years it was used for various other purposes: a garage and even, during the polio pandemic, as a vaccination center. But it seemed like its owners had no interest in maintaining the structure, so it gradually moldered away, the wooden roof with its lovely neo-Mudejar motifs disintegrating in the rain.

Happily, a group of locals and architects banded together and lobbied for the building to be restored to its former glory. To everyone’s amazement, the city council answered their prayers and a full restoration is now coming to completion. The building itself cost 30 million euros to acquire and a further 8 million or so to restore. On the tour I took of the venue our guide explained that when they began, the pelota court had become a jungle and roof had to be discarded entirely. However, the main structure, despite a lot of crumbling brick, was more or less intact and, the gorgeous ironwork holding up the stands had hardly rusted at all (though to keep to present-day building codes, extra iron supports have been added). The roof, of course, had to be replaced, but the reproduction is breathtaking and, incredibly, survived storm Filomena last winter.

As Basque pelota is still played professionally in other parts of the world, some were hoping that the sport could be played here, but the court isn’t yet up to standards. However, as the building work wraps up (its completion was delayed due to the pandemic) there are plans to use the 4,000 seater stadium as a venue for other events. An outdoor cinema, which would make use of its high white walls, is a strong contender. In the meantime, if you want to take a look inside, you’ll have to wait until the council issues more tickets for tours. Demand has been so high that at the time of writing, all current tickets have been sold out.

If you are venturing into Madrid and would like to know a little bit about the history of the city, how about booking yourself in for a unique walking tour with me, the writer of The Making of Madrid?