When I heard that an observation deck had opened up next to the Royal Palace, I was down there like a shot. Closed off to visitors for years, up until now it had only been possible to get tantalizing glimpses of its spectacular views through iron railings. So it was a delight to be finally staring out across the plain that stretches from Madrid all the way to the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains.

Stunning views

Looking towards these snow capped peaks, I found myself dreaming of the time when Madrid was a garrison town built to protect the citizens of Al-Andalus from the Christian hordes that lived in the north, beyond the mountains.

From the second half of the 9th century, Madrid was part of a string of watchtowers that Mohammed of Cordoba ordered to be constructed to protect Toledo from invasion. Built along an old Roman road, one of these original towers can be found at Torrelodones, and another at Alcalá de Henares. Like many Spanish terms, the Alcalá from Alcalá de Henares derives from an word Arabic: Al-Qalat meaning fortress.

While Madrid’s fortress or Alcazar was burnt down in the 18th century, the base of one of Madrid’s watchtowers is still intact and on display in the car park beneath the Plaza de Oriente!

Invasion from the north

Madrid was known at that time as Mayrit, a name which means plentiful waterways in Arabic. And it was probably the abundant natural springs running underground that allowed the population to grow into a walled town of 3,000 that boasted a medina and its own mosque. However, disaster struck in 1083 when Alfonso VI of León and Castile took the town by force on his way to capture the more important prize of Toledo.

Surrounding the watchtower and medina, the walls of Mayrit were in places as high as 11.5 meters. However, Alfonso’s nimble troops somehow managed it to scale this obstacle with catlike agility. Some say that this is the reason why Madrileños are called “gatos” (the Spanish word for cats).

To get an idea of the difficulty of this climb you can view a small section of this wall at Parque Emir Mohamed. A short stroll from the palace, it’s located right by Almudena cathedral’s crypt.

A “miraculous” find

To legitimize the invasion, Alfonso needed to prove that Mayrit had already been a Christian settlement and that he was freeing the Christians living under Islamic rule. “Miraculously” a statue of the virgin was found in the walls of the almudena (the Arabic word for fortress) and paraded about the town before Alfonso rode off to take down Toledo, which for him, was the real prize (check out my previous post for more on the Virgin of Almudena).

It seemed like the “reconquista” of Madrid was a done deal. However, these were volatile times and when Alfonso died in Toledo in 1109, Almoravid troops led by Alí Ben Yusuf marched towards Mayrit. Camping out below the town’s walls, they staged an unsuccessful attempt to take Mayrit back. Now, this area is called Campo del Moro, that is the Moor’s field. Part of the palace grounds and landscaped to resemble an English garden, it’s a wonderful place to spend a tranquil afternoon.

Dreaming of Al-Andalus

Campo del Moro is also visible from the observation deck mentioned at the beginning of this article. So if you do happen to pass by, it’s worth taking the time to think back to the days when the call to prayer threaded through the streets of Mayrit’s medina.

If you’d like to learn more about Muslim Madrid, you can book a private tour with me that follows the fate of the city’s Islamic community from when Madrid was part of Al-Andalus up until the forced conversions of 1502.

Pingback: Ten Truly Madrileño Terms - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Three Museums that Reveal Madrid Through the Ages - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: The Reconquest That Never Was - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Five Things You Didn't Know About Madrid - The Making of Madrid

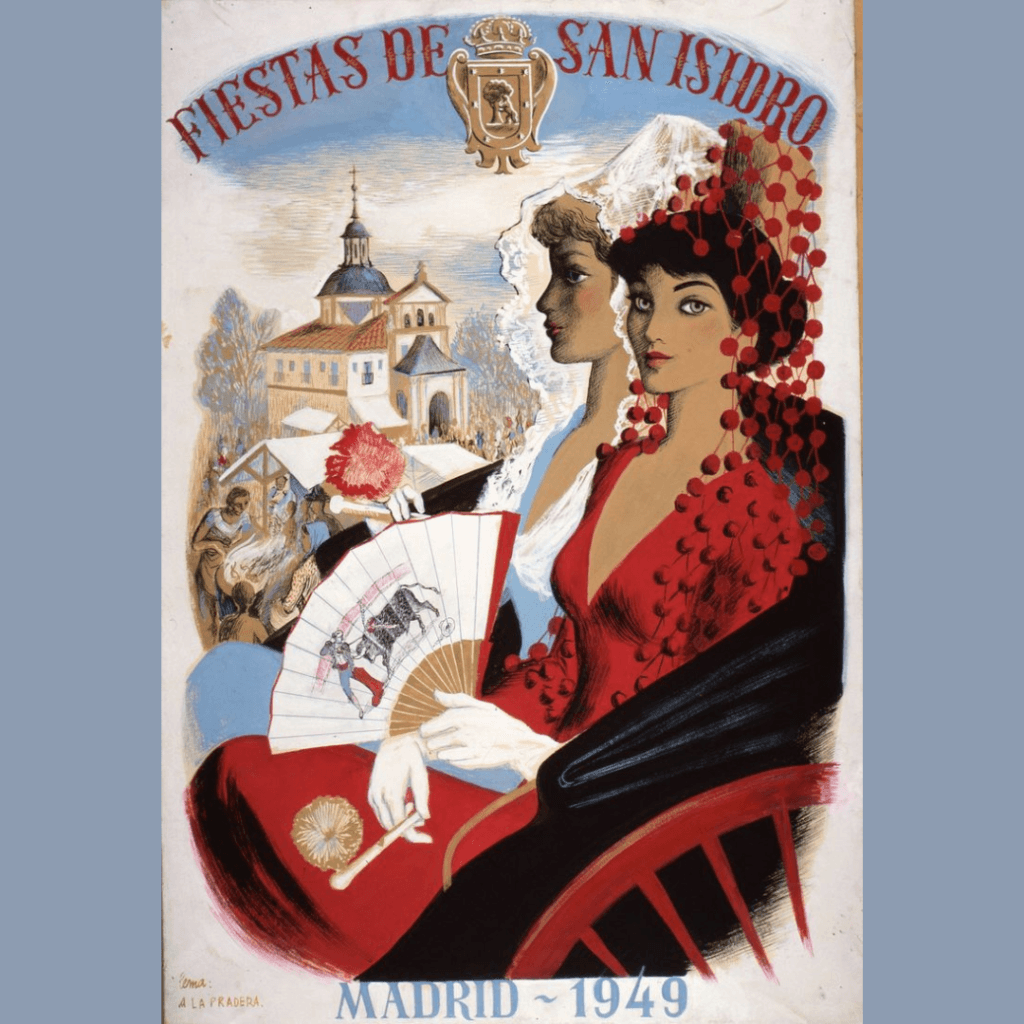

Pingback: San Isidro Madrid's (male) patron saint - The Making of Madrid