In Madrid’s Royal Academy of History lies a document that has had scholars of Spanish literature up in arms ever since it was discovered in a dusty archive in Valladolid back in 1840. Dated September 1569, it’s an order for the arrest of a “certain Miguel de Cervantes” accused of gravely wounding Don Antonio de Sigura while dueling. The victim’s injuries were apparently bad enough to merit a severe punishment and once captured, Cervantes was not only to have his right hand amputated, but was also to be sent into exile for 10 years. While this is the only answer we have as to the mystery of why Cervantes left Spain for Rome in his early twenties, many scholars prefer to disregard this document, saying that there is no evidence to suggest that this was the Miguel de Cervantes, illustrious author of one of the most groundbreaking books in history.

Personally, I think it’s highly likely that this was the Cervantes we are all familiar with, and that his violent conduct was no different to many of his contemporaries. Because while dueling had long been officially outlawed in Spain by Ferdinand II of Aragon, swords were so frequently drawn in the 16th and 17th centuries, that corpses were not an uncommon sight on Madrid’s streets.

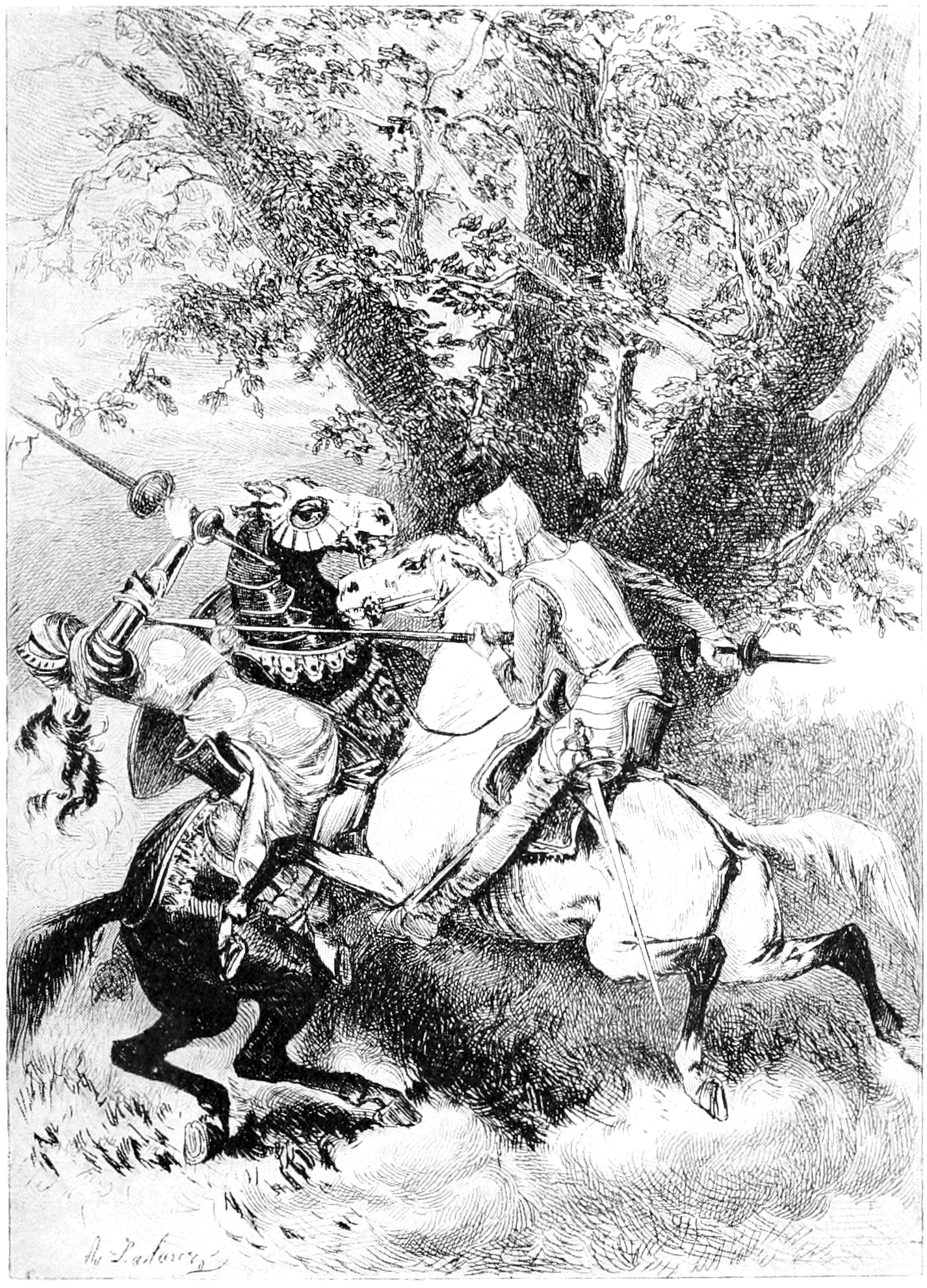

This was at the height of the Spanish Empire and troops on leave from the Americas or the battlefields in Europe flooded Madrid. All were armed, unless they were visiting the city’s numerous brothels where they were legally required to hand in their weapons before entering. This was to stop them from dueling. Despite many of them frequenting these houses of ill repute, young men prided themselves on following medieval codes of chivalry. Fights could break out over just about anything, but were generally resolved upon drawing blood. They could only be to the death if you had been cuckolded, or someone had bad mouthed your wife or mother. The absurdity of sticking to such antiquated noble codes is of course heavily satirised in Don Quijote, which Cervantes wrote many years after his youthful misadventures.

If the writer was, indeed the Cervantes who had badly wounded another man while dueling, he did eventually receive his just deserts. Though he escaped from the clutches of Madrid’s bailiff by running abroad, to prove his valour and perhaps to win a pardon, he famously took part in the sea battle of Lepanto in 1571 and, after taking several shots to the chest and arm, lost the use of not his right, but his left hand. Lucky for us, as this uninjured hand was the one he was to write his greatest work with.

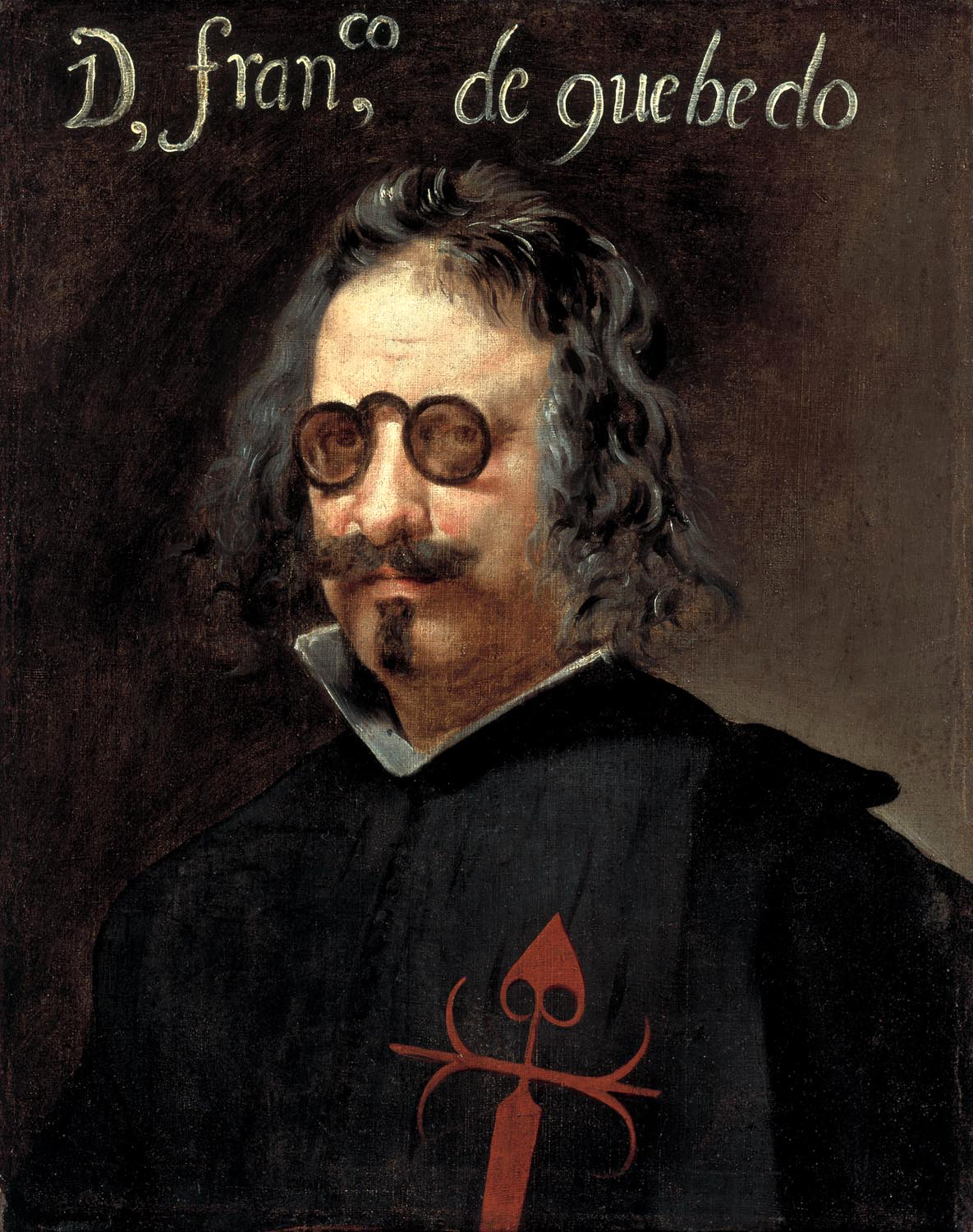

Cervantes wasn’t the only literary figure to be involved in dueling. His contemporary, Francisco de Quevedo, was very handy with a sword and it’s said that he fought with the author and fencing master Luis Pacheco de Narváez in 1608. Narváez had challenged him to a fight after Quevedo had insulted one of his works, however, Narváez’s pride was further injured when Quevedo removed his opponent’s hat with the tip of his sword, bringing the duel to a close. Quevedo even got away with murder in 1611! After witnessing a man slap a woman on the cheek in the church of San Martín, he rushed after the brute and ran him through with his sword on the street, mortally wounding him. Punishment for dueling included exile, being set to work as a galley slave, or even death. However, as Quevedo was a well-connected aristocrat, it seems he could pretty much do as he pleased.

With all this fighting going on, any gentleman worth his salt had to know how to handle himself with a sword. In fact, the Spaniards were famous throughout Europe for their fencing skills, skills that had often been honed overseas in battle. One of the hallmarks of this style was fancy footwork and feints, while another was the use of both a sword and dagger while fighting. The dagger would usually be held in the left hand, while in the right would be a ropero or rapier. In street fights, cloaks could be wound around the arm and used as a shield, or be thrown over an opponent to neatly net them.

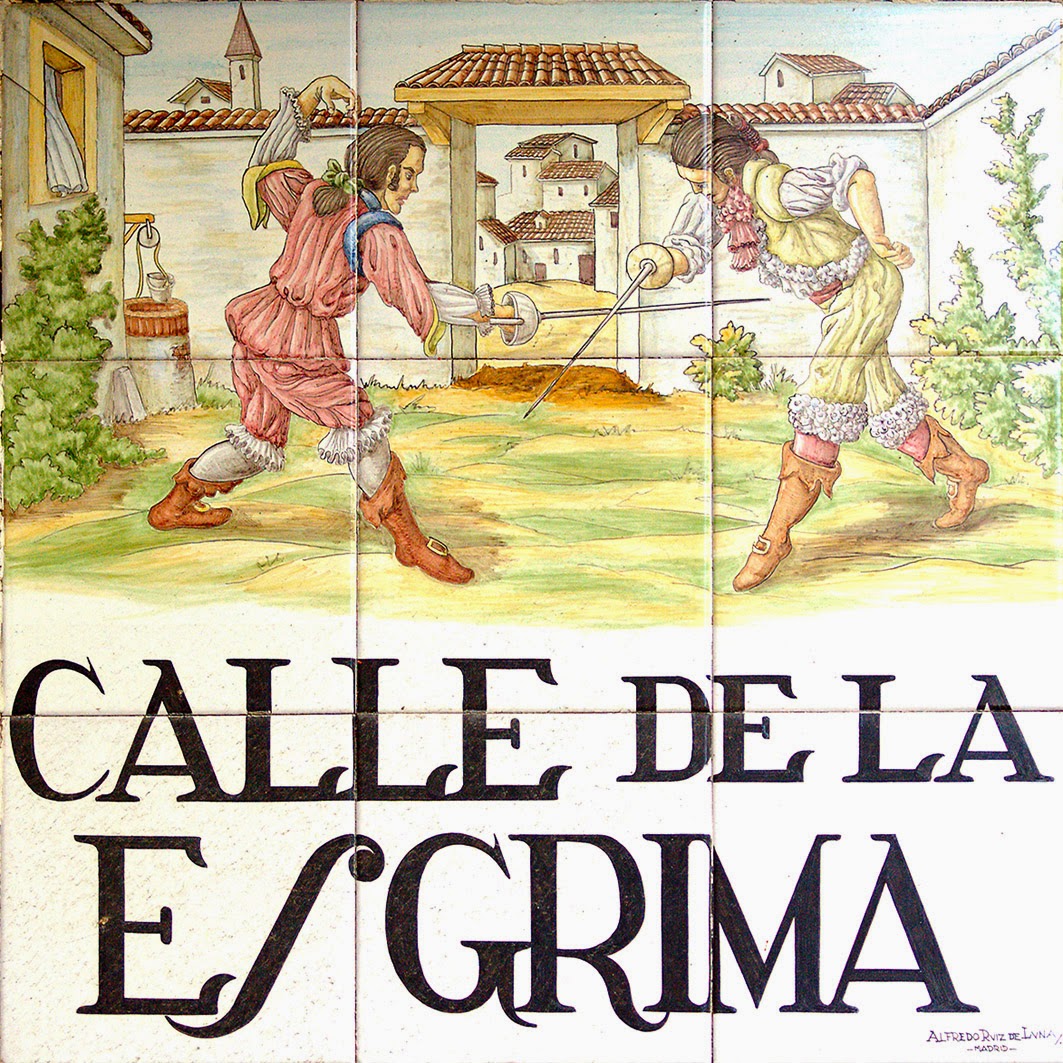

Fencing schools were all over the city and one particularly famous establishment was located in Lavapiés. The story goes that the school first set up shop in Calle de la Espada, with the master hanging up a sword (rumoured to have once been the property of a French nobleman) outside the premises. The street was later named after this very sword, which remained on display for years after the master had been kicked out for non payment of rent. Undaunted, said master set up shop round the corner in what is now known as Calle de la Esgrima, or the Street of Fencing. Word got round that this was one of the best schools in the city and wannabe warriors would turn up to try their hand against its pupils, who often practised outside. This led to so many street brawls that the master was ordered by the authorities to conduct his classes indoors.

You can still learn 17th century sword and dagger fighting at Esgrima Histórica Madrid. It’s run by a chap named Alberto Bomprezzi, who, according to his profile, is fluent in English, French and Italian, and, with his muscular build and salt and pepper hair, looks just like a dashing caballero of old!

Footnote: To write the parts about Cervantes and his arrest warrant, I referred to the book “Cervantes en Madrid Vida y Muerte” by Juan Antonio Cabezas.

If you’re interested in the history of Madrid and are visiting or live in the city, you might want to book yourself in for one of my unique walking tours.

Pingback: Gangs of Madrid: Is Madrid a Safe City? - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Street Signs in Madrid: a Brief History - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Cervantes: The Ultimate Late Bloomer - The Making of Madrid