Updated January 2026

Anyone who finds themselves in the lobby of the newly refurbished Sevilla metro is in for a treat. Finally exposed after being hidden for 50 years is the svelte figure of a sassy flapper from the 1920s. The text accompanying her reads: “Sales de Carabaña soap, unbeatable for the skin.” It’s an advertisement that dates right back to when the metro was first constructed (1919 to 1936) and companies paid to have their brands immortalised in tile upon its walls. Well, immortalised until the 1970s that is, when renovation work meant that all these old ads were covered up. Which is a pity, because the artists working on them were part of a golden age of ceramic art that took the capital by storm.

The golden age of ceramic art begins with the Arts and Crafts movement

The advert in metro Sevilla is the work of Alfonso Romero Mesa, one of the most famous ceramic artists working in the early 20th century, and former apprentice to the maestro, Enrique Guijo whose work, even to this day, can be seen about town. Guijo, like many other artists involved in the Arts and Crafts movement, was interested in reviving traditional crafts that were being threatened by industrialisation. Born in Cordoba in 1871, when he first arrived in Madrid he worked as a specialist in the restoration of ceramic art for the city’s Museum of Archaeology. However, a trip to Talavera in 1907 convinced him of the need for a revival of ceramic art. Though the city had been famous for its production of traditional ceramics, he discovered that the number of workshops there were dwindling. Studying what he could about production techniques, he soon founded his own factory in Madrid with another Andalusian ceramicist Juan Ruiz de Luna (whose grandson, Alfredo Ruiz de Luna González, incidentally, was the man responsible for making the tiled street signs all over Madrid). In this way the golden age of ceramic art began.

Ruiz de Luna-Guijo and Co

The mission of Ruiz de Luna-Guijo and Co. was to revive the Talavera tradition. At first, things went splendidly; they scored work with prestigious clients, such as the artist Joaquín Sorolla, who commissioned them to work on his garden in the centre of the city (check out my post on secret gardens for more information). However, Guijo was frustrated, because Ruiz de Luna seemed happy simply to imitate the styles of the past and had little interest in innovation. In 1917 the two split and Guijo set up another company with his nephew, daughter, and a promising young apprentice, Alfonso Romero Mesa.

The metro and more

From that point on Guijo and Romero mainly dedicated themselves to commercial work, winning a contract to work on the advertisements for the metro and also producing stunning tiled facades for shops and bars. They were even asked to produce the tiles for the new slaughterhouse, the enormous Matadero (now an arts centre).

One of most impressive jobs the two ever did brought Guijo briefly back together with his former partner, Ruiz de Luna. Los Gabrieles was a bar which had opened in 1908 and it’s here that Guijo, Romero and Ruiz de Luna came together to work on the interiors, which are, judging by this article in El Pais, absolutely stunning. The tragedy being that it had to close during the last economic crisis and is currently shut to the public.

Creative differences

Guijo and Romero’s partnership came to an end in 1923 when Guijo was passed over for a contract to work on Las Ventas bullring, the job going to his apprentice instead. It seems that a bitter row over who had actually drawn the sketches for the job was at the heart of this split, with Romero claiming Guijo had fraudulently signed his name to sketches he hadn’t done and Guijo denying these charges, claiming the reverse was true: that Romero was trying to take credit for his work.

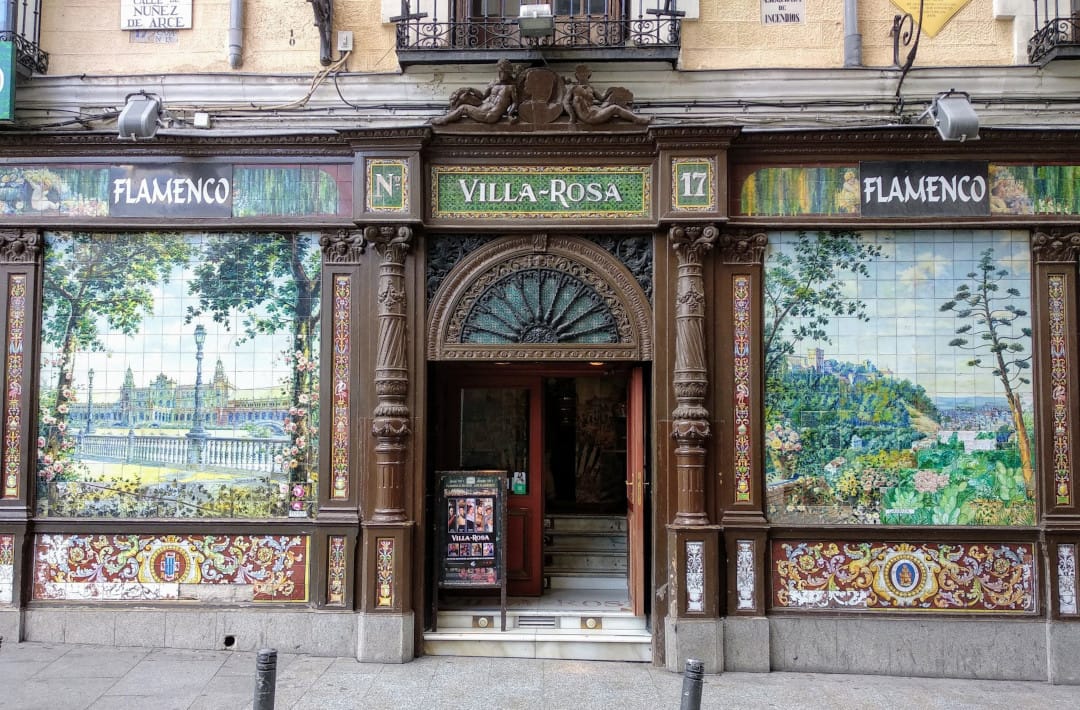

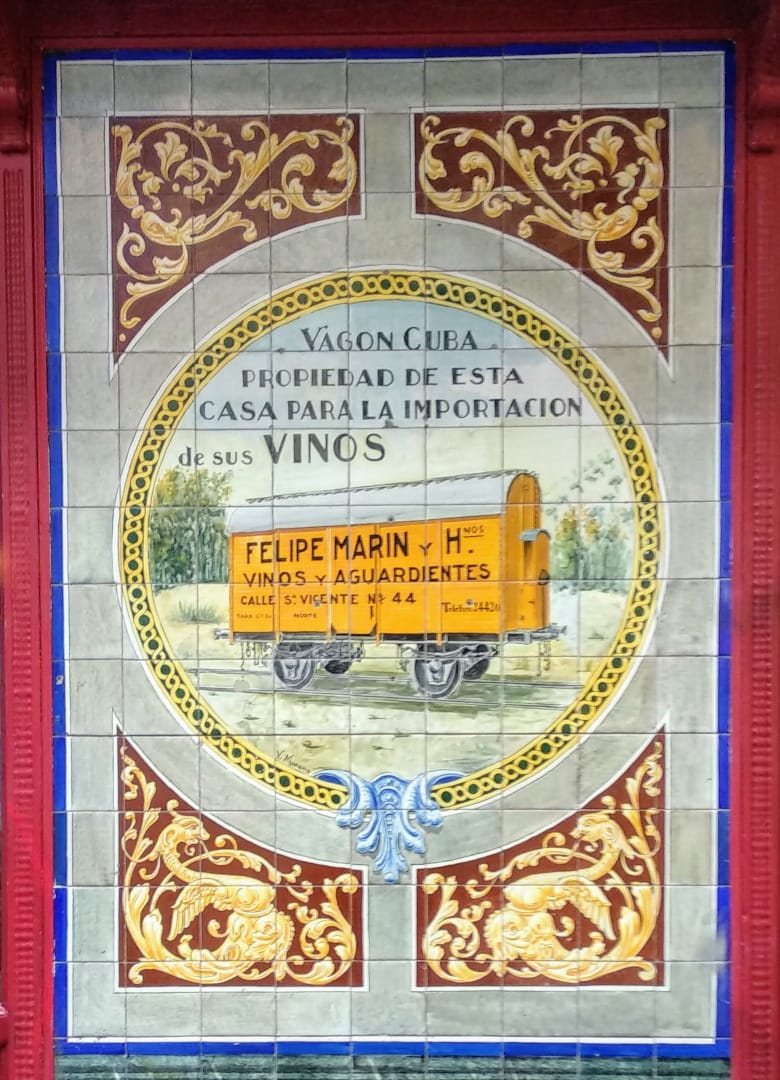

Romero’s career went from strength to strength after this and he was given the job of decorating the exterior of Villa Rosa, a flamenco bar that opened in 1911. This huge tiled facade can still be seen to this day by those passing through Plaza Santa Ana. You can also see his handiwork in the tiled advertisements that are still on display outside Bodegas Rosell.

Fading into obscurity, the end of the golden age of ceramic art

Meanwhile, Guijo had donated his ceramic collection to the Museum of the History of Madrid in 1926 and was given a post as a curator. A good deal, because as part of the package he got himself 10 rooms on the second floor of the building. His business went to his successor, Angel Caballero. It’s said that Guijo sat the Civil War out in the museum and remained at his post until he retired in 1944, completely blind, living out his final year on the planet in obscurity, completely forgotten by a world that had moved on.

If you’d like to see Guijo’s work for yourself, I highly recommend going to take a look at the colourful advertisements he did for the Hueveria and Farmacia Juanse (lead image) in Malasaña, right round the corner from where Guijo spent his final years. The latter was covered up for a long time during Franco’s dictatorship, when any business with exterior advertising (even if it was for a long-defunct product) had to pay extra taxes. The result was that many of Madrid’s gorgeous tiled facades were covered up in paint or plaster, some of course, ruined for ever, but others, like Farmacia Juanse, lovingly restored for posterity.

I’m glad to say that these tiles are now well cared for, in fact, I just added the above photo after walking by Juanse in 2026 and meeting a restorer who was hard at it. Her team had removed all the graffiti and were repainting spoiled sections!

If you enjoyed this article and are interested in finding more about about the city, why not book in for a unique walking tour with me, the author of The Making of Madrid.

To write this post I am deeply indebted to Antonio Perla’s book “Ceramica Aplicada en la Architectura Madrileña“. Published in 1988 it details all of the surviving works from Madrid’s golden age of ceramics. Sadly, Google street view revealed that many of these pieces are now lost to posterity. Below are some surviving works I managed to capture done by other artists during the same period.

Great article. You will be pleased to learn that the Gabrieles is about to undergo refurbishment, including restoration of the remaining paneles of tiles (which are spectacular) , and should reopen in 2021.

One minor correction. Villa Rosa, opened in 1911, by 1921 at the latest was a venue for flamenco.

Hi Justin. That is, indeed, great news and thank you for the correction, I’ve double checked and amended the article. Can’t wait to see the inside of Gabrieles!

Pingback: Madrid's Oldest Stores - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: SiteTitle Madrid’s Oldest Stores | Travel Secrets Magazine