The Allegory of the Town of Madrid is not one of Goya‘s best paintings. Classical in style, there’s little to hint at the innovative verve of his later Black Paintings, nor any reflection of the tenderness of his earlier portraits of working-class Madrileños. But, if you know a little bit about its history, this canvas is absolutely fascinating because of what it reveals about not only Goya himself, but about the political climate of his time.

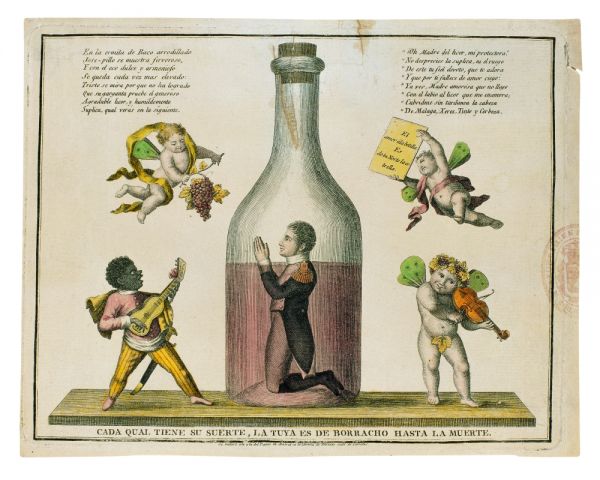

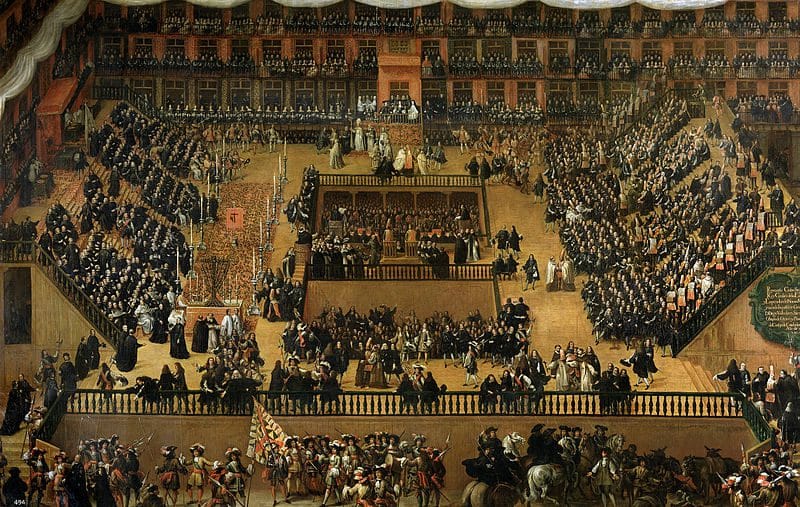

The painting was originally commissioned in 1808 by the new French king Joseph Bonaparte. This was shortly following the French occupation of the city on March 23 the same year. Goya might have been more than a little bit relieved by this regime change, because he’d just been put on trial for obscenity by the Spanish Inquisition who had seized and confiscated La Maja Desnuda from the collection of Manuel Godoy.

Goya’s depiction of the saucy maja was considered particularly shocking for its subject’s unflinching gaze and open display of pubic hair. However, he managed to escape prosecution by claiming that the nude was following in the artistic tradition of Titan and Velazquez. Still, he must have been more than a little relieved when Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte came to the throne and abolished the Inquisition in December 1808.

Goya easily adapted to the new regime and, while avoiding making any public statements concerning his political affiliations, was happy to paint portraits for the new court, just as he had previously done for the Bourbon monarchy. So, without any fuss, he got to work on his new commission and delivered the portrait in 1810. In the original picture, Joseph’s head was placed inside an oval medallion flanked by two male figures representing Fame and Victory.

Though many liberal members of the upper classes secretly supported Joseph, he was hated by the populace at large. Ordinary citizens even rose up against him on May 2 1808 setting in motion the War of Independence. But it wasn’t until 1812 when Wellington defeated the French troops in the Battle of Salamanca that Joseph was forced to leave. The town council then asked Goya to erase the portrait of Joseph and replace it with the word “Constitución” to honour the passing of Spain’s first constitution by the Cádiz Cortes. Goya, ever obliging, complied, but, months later, Joseph returned to Madrid and the painting had to be altered again. This time Felipe Abas, one of Goya’s pupils, removed the paint and repainted Joseph’s portrait.

Only Joseph’s days were numbered and he left the city again in 1813, this time for good. Another of Goya’s students, Dionisio Gómez was given the job of painting “Constitución” back over the defeated French leader’s mug. But this still wasn’t the end of the revisions. When the War of Independence ended in 1814, the odious Ferdinand VII came to the throne and abolished the new constitution reinstating absolutist rule.

The word “constitution” was again rubbed out and the face of another king put in its place. This time Ferdinand VII. It’s thought that Goya, probably thoroughly sick of this painting by this point, probably didn’t paint the new king’s portrait and left the job again to a pupil. However, the result was just as ghastly as the actual portrait he did of Ferdinand that hangs in the Prado to this day. It was decided, of course, that the portrait had to be repainted!

By this time however, Goya was long gone. He’d already been retreating from society, living in Quinta del Sordo between 1819 and 1823, where he painted his Black Paintings. But in 1824, he decided to abandon Spain for good and settled in Bordeaux. While he never expressed his political views, it’s thought that he had become increasingly disenchanted with the oppressive atmosphere in his native country. That’s why the job of repainting Fernando VII went to Vicente López.

But the story doesn’t end there, because in 1843, the constitution again replaced the king. Then, in 1873, after Isabel II had been deposed, the liberal mayor of Madrid, Marqués de Sardoal ordered that the multiple layers of paint in the medallion be completely stripped away and the words Dos de Mayo (May 2) be put in, commemorating the sacrifice Madrileños made in their uprising against the French. In this way he reasoned, subsequent political regimes could not find fault with this artwork again!

The Allegory of the Town of Madrid remains in this final form on permanent display at the Museum of Madrid. An unremarkable canvas that tells an incredible story. If you’d like to get a visual idea of how the painting changed, take a look at the opening segment in the video below:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QLMdC1KHAnI&w=560&h=315]

If you enjoyed this post and would like to find out more about the history of Madrid, why not book yourself in for a unique walking tour of the city?

Pingback: Dos de Mayo: The Madrileñes Strike Back - Confused Heap of Facts