Psst! Want to buy a blade? Es muy fácil my friend. Just go to the south western corner of Plaza Mayor, enter the Arco de Cuchilleros and head down the steep street – you’ll know you’re in the right place as soon as you catch a whiff of the slaughterhouse – there you’ll find all manner of knives and swords on display. Blades fine enough to cut clean through muscle and even bone! Handmade by artisans and available for a fair price, they’re the best the city has to offer. Only there’s one slight catch, you’ll need to get hold of a decent a time machine to get there. Set it back 200, no, lets say 300 years and you’re sorted!

The Arco de Cuchilleros

The Arco de Cuchilleros

Ahhh, if only it were possible to take a stroll around the filthy yet fascinating streets of 18th century Madrid! A city in which commerce was dominated by guilds. Each neighbourhood or street devoted to the sale of one particular item or service. Sadly, of course, that’s not an option, but if you look up at the beautiful tiled street signs in central Madrid, you can still identify some of these areas. The Calle de Cerrajeros, for instance, where locksmiths plied their trade, or the Calle de Tintoreros where you went to have cloth dyed, or the Calle de Esparteros, where baskets, espadrilles and rope fashioned from esparto grass were sold (esparteros still exist these days, by the way, just not in the Calle de Esparteros, but around the Calle de Toledo).

In post medieval Spain, guilds still held sway over the commercial life of the city. By clubbing together, tradesmen had the power to fix prices, keep out the competition, and regulate the quality of items and services sold. Perhaps most importantly, they could also support members who had fallen on hard times. The downside of all this was that it was a deeply nepotistic system with apprenticeships generally going to firstborn sons. Those who weren’t members of a guild recognised by the crown, simply could not do business.

Button makers to the king

The wealthiest guilds in Madrid served the court directly and were located close to the palace around the Plaza Mayor. In addition to the Cuchilleros, who furnished noblemen with their swords and butchers with knives, there was the Hileras who manufactured gold thread for embroidered detail, and the Botoneras, or Button Makers.

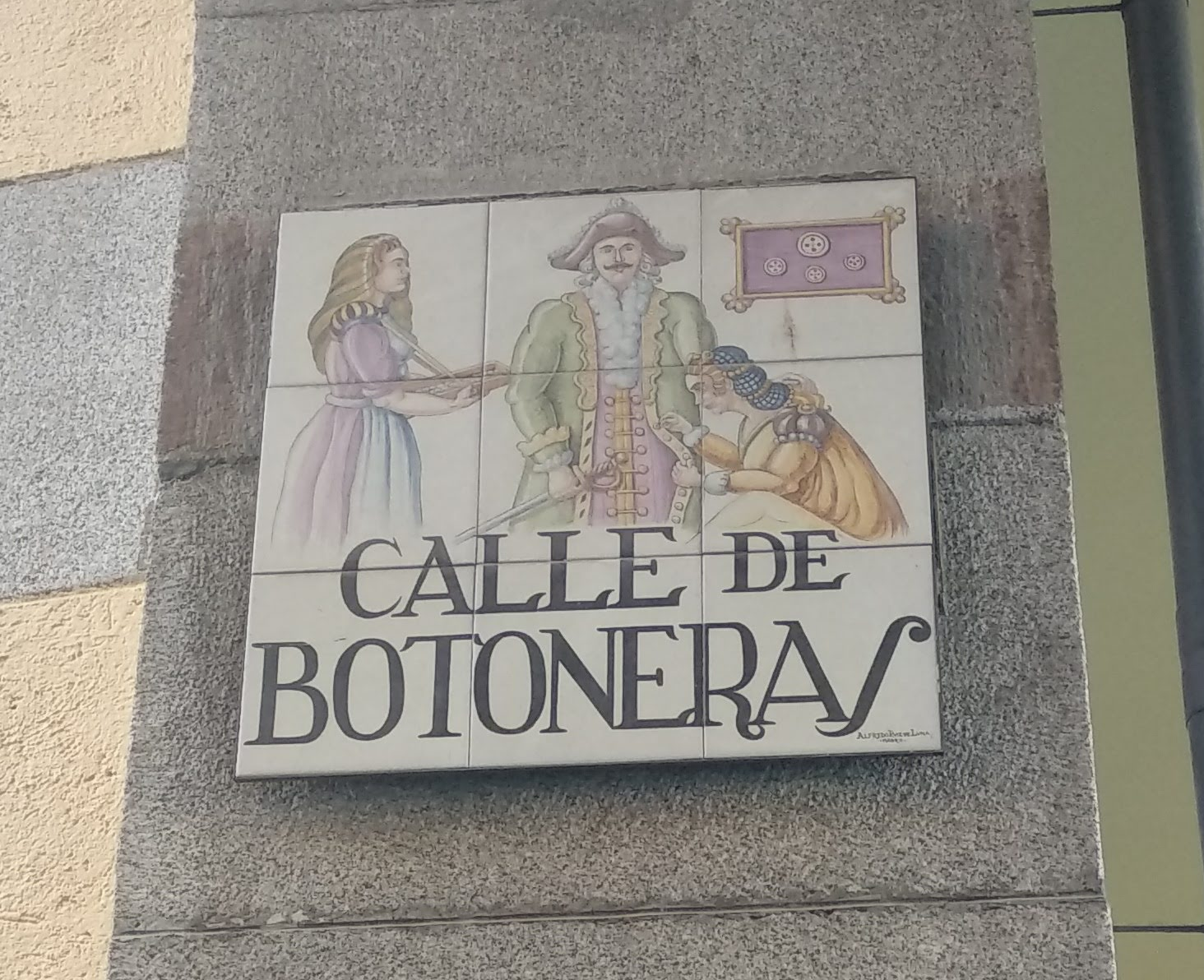

The street of the Button Makers

The street of the Button MakersThe artisans who formed the Botoneras guild were renowned for producing beautiful hand-crafted buttons of gold, silver, bone, and brass; the kind of item that can still be spotted in the detail of Velazquez’s portraits of royalty. Gleaming confections that not only served a practical purpose, but were also the ultimate status symbol and by consequence the limited preserve of the very wealthy. Surprising then that this lucrative trade was one of the very few controlled by women. The only other two female-run guilds in the city dealt with cigarette production and the city’s laundry, tasks that placed them much further down the social pecking order.

Besides making gorgeous buttons, the Botoneras were also incredibly well-informed about goings on within the court. If you wanted the inside scoop, these were the ladies to consult. Unfortunately this knowledge landed them in hot water when they got caught in the middle of a spat between Philip IV and his wife Isabel of Bourbon.

A royal row

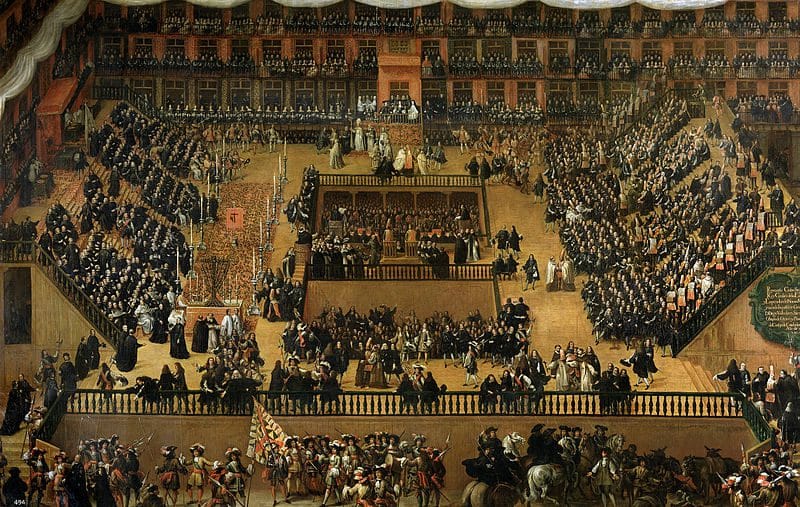

In the 17th century bullfights, autos de fe, and plays were held in the Plaza Mayor. While the common folk watched from the ground, the nobility sat in the balconies surrounding the square. The queen, having caught wind of her husband’s affair with the actress “La Calderona,” forbade anyone to allow the king’s mistress access to any of these balconies. So imagine her fury then when she turned up one day to see La Calderona sat in an adjacent balcony! She went straight to the Botoneras to find out who had permitted this outrage. They, in turn, revealed that the king himself, pining for a glimpse of his mistress, was the guilty party. When he heard that the Botoneras had blabbed, the king revoked the guild’s license. It wasn’t until the queen interceded on their behalf that it was restored.

Super guild

Once the Botoneras had weathered that particular storm, they went on to triumph by banding together with other powerful guilds to form a kind of super guild that managed for a time to withstand the challenges of a changing economy. To maintain their monopoly on the market, an organisation made up of Madrid’s jewellers, haberdashers, silk merchants, textile merchants, and pharmacists, was established in 1667. The Cinco Gremios Mayores de Madrid (Five Major Guilds of Madrid) sought to trade internationally, gradually pulling away from the original guilds’ artesanal roots and becoming so powerful that by 1789 it had the funds to build a handsome head office just near Plaza Mayor (a huge building that still stands to this day).

La Casa de los Cinco Gremios Mayores (The House of the Five Main Guilds)

La Casa de los Cinco Gremios Mayores (The House of the Five Main Guilds)Only by banding together could these guilds resist the growing trend towards a free market economy that was sweeping the globe during the 1700s. But the writing was on the wall with guilds first being briefly banned by the progressive Cortes of Cadiz in 1812, then comprehensively outlawed under Isabella II between 1834 and 1836.

Gone but not forgottenThe abolition of guilds coincided in 1835 with many of Madrid’s streets being renamed. Ironically, some of these names indicated where the now defunct guilds once stood. Nevertheless, Pontejos (an area named after the mayor that presided over this change) is one of the few zones in central Madrid that still retains some of the character it must once have had. Right by Plaza Mayor, it’s a dressmaker’s dream come true with many of its streets lined with haberdashers and textile shops, just as it would have been when the swells at court went there to get their new threads made.

A haberdasher’s display in Pontejos, an area that retains some of the character it once had when guilds ruled Madrid’s commercial life

A haberdasher’s display in Pontejos, an area that retains some of the character it once had when guilds ruled Madrid’s commercial life

Another area that has retained its former character is the Calle de la Ribera de Curtidores (tanners). While there are no longer any tanners in the district, the street is still lined with shops selling high quality leather. The name for the Rastro market held there on Sundays, is said to derive from the days when a “rastro” or trail of blood left by the animal carcasses dragged up from the city’s main abattoir (located beside the Manzanares) trickled down the street. Back in the day this bloody trail would have led all the way up to the Calle de Cuchilleros and the adjacent meat market.

Have you spotted any street signs bearing the names of long lost guilds or do you know of any artesanal shops in Madrid with an interesting history? Leave a comment below, I’d love to hear about it.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to find out more about the history of Madrid, why not book yourself in for a unique walking tour of the city?

Great post as always Felicity! I’d noticed the streets named after old professions, but I didn’t know anything about the guilds.

Pingback: Madrid's Oldest Stores - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: A Peek Inside Banco de España - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: A Brief History of the Rastro - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: SiteTitle Madrid’s Oldest Stores | Travel Secrets Magazine

Pingback: Why is Madrid the capital of Spain? - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Pontejos: stitching together Madrid's past and present - The Making of Madrid