Have you ever been to Pepe Botella? This traditional bar looking out over Plaza Dos de Mayo is, in my opinion, one of the best places in the city to spend a tranquil morning writing. But do you know what the significance of this bar’s name is and what exactly happened on the second of May? The answers to these questions and more can be found below:

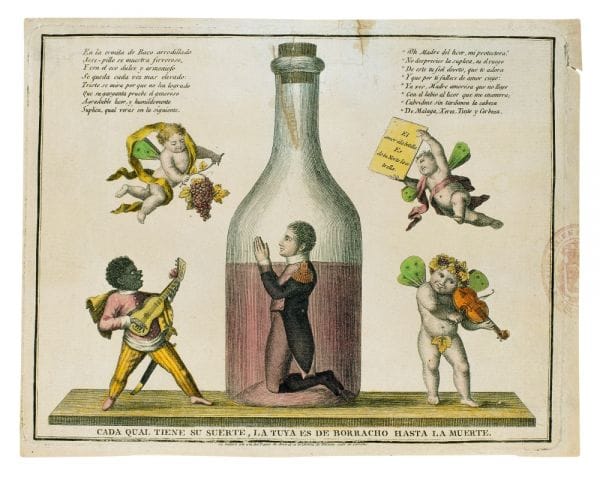

A tipsy tyrant?

Pepe botella was the unaffectionate nickname given to Joseph Bonaparte by his Spanish subjects during his brief rule. Pepe being the equivalent of Joe and botella referring to the bottle that their new king reputedly had a great fondness for. But this epithet says more about how tragically misunderstood Joseph was, than the vices of the man himself. The truth was that he was a practically abstemious man with high ideals and little stomach for warfare. Installed in the throne in 1808 by his younger brother Napoleon, Joseph hoped to improve the lot of the common man by putting into practise a Republican constitution that embraced the creation of an independent judiciary among other innovative liberal ideas. He’d already demonstrated a remarkable modernizing zeal during his reign as king of Naples, where he’d made quite an impact by abolishing feudal privileges and taxes. However, upon his arrival in Spain he found himself being thwarted at every turn by a populace who were understandably peeved at the French army’s summary occupation of the country.

A popular uprising took place in Madrid on May 2 1808 compelling Joseph to respond with force. The carnage that ensued plunged Spain into a long and brutal conflict. Busy fighting a war on numerous fronts, Joe didn’t manage to make much of an impact on Spanish politics, but he did leave a lasting impression behind on Madrid. Another of Joseph’s nicknames was Pepe Plazuelas and this was earned for his work creating some of the city’s most well-known public spaces; Plaza Santa Ana and Plaza Oriente to name but a few. By demolishing numerous churches and monasteries he opened up the city’s cramped medieval streets to create wide boulevards and squares. This left him with a huge amount of artwork on his hands. Rather than sell it off, he decided to put it on display to the public at El Palacio de Buenavista. Though these works eventually formed the basis of the Prado’s collection, Joseph was forced out before his plan ever came to fruition.

The escape tunnel

An alliance between British and Spanish forces in 1813, expelled the French from Spain once and for all and Joseph left with his tail between his legs. Though he had tried hard to get the Spanish to love him, he was always aware that defeat was on the cards. So much so that he had an escape tunnel constructed between the palace and the Manzanares River (which, according to ABC Madrid, is due to be opened to the public in 2019). Joseph was succeeded by Ferdinand VII, a rather odious man who rolled back many political developments including scrapping a modern Constitution that was drafted in Cadiz by the rebels loyal to the king, quickly reinstating the dreaded Inquisition and abolishing an independent judiciary. With little thought for the terrible suffering his people had gone through to put him back on the throne, he insisted on wielding absolute power and suppressed the liberal movement putting Spain way behind its more enlightened European neighbours.

The awful aftermath

During Ferdinand’s reign, those Spanish sympathetic to Joseph Bonaparte’s ideals, namely the afrancesados, had to flee abroad or face imprisonment. The many Spaniards who had collaborated with the regime, now carefully hid any traces of having fraternised with the enemy. In 2011, for instance, X-rays of Goya’s 1823 portrait of Don Ramón Satué revealed a shadowy figure underneath in full French military regalia. A general who may well have been Joseph Bonaparte. It’s thought that the artist had deeply divided feelings about this would be benevolent dictator. A liberal himself, he supported the aims of the regime, but having seen at first hand the brutal response to the May 2 uprising, he couldn’t have felt very fond of the French oppressors. Indeed his Disasters of War print series is an indictment of the cruel behaviour he witnessed. However, they also deal with Goya’s disappointment at the suppression of the liberal cause during the reinstatement of the Bourbon monarchy, hinting perhaps that he might have secretly been rooting for Pepe. Who knows, if Joseph had been given half a chance, his brand of enlightened absolutism could have changed Spain for the better.

Keen to find out more about the history of Madrid? See another side of the city with one of my unique walking tours.

Pingback: Madrid's Most Problematic Painting - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Three Museums that Reveal Madrid Through the Ages - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Three Myths About the Spanish Inquisition - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Trials of faith in Plaza Mayor - The Making of Madrid