Updated January 21, 2026

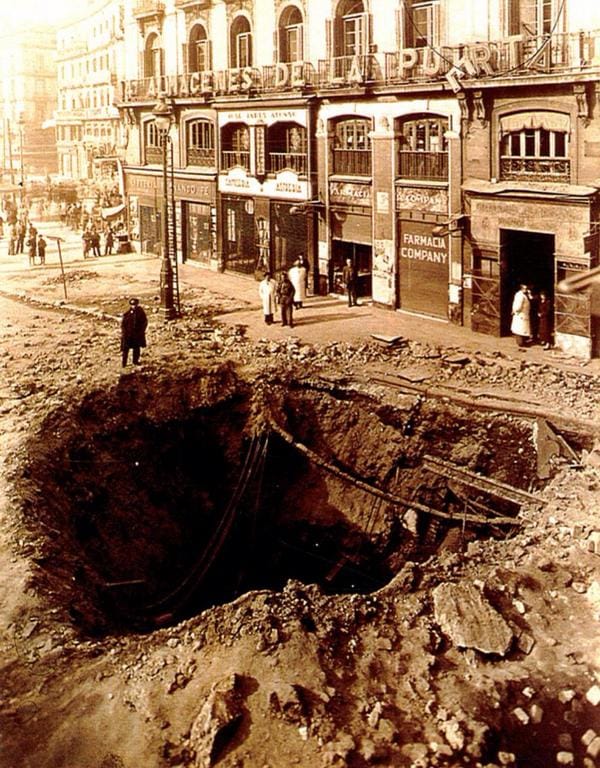

Though the siege of Madrid lasted two and a half years, today the city bears few visible scars. As the bomb craters were filled in, a silence fell over the cowed populace. A silence that until recently has largely remained unbroken. And yet, out on the edges of the city where the battle raged the fiercest, it’s still possible to find grim reminders of a time when Spain was irreconcilably divided.

How the siege went down

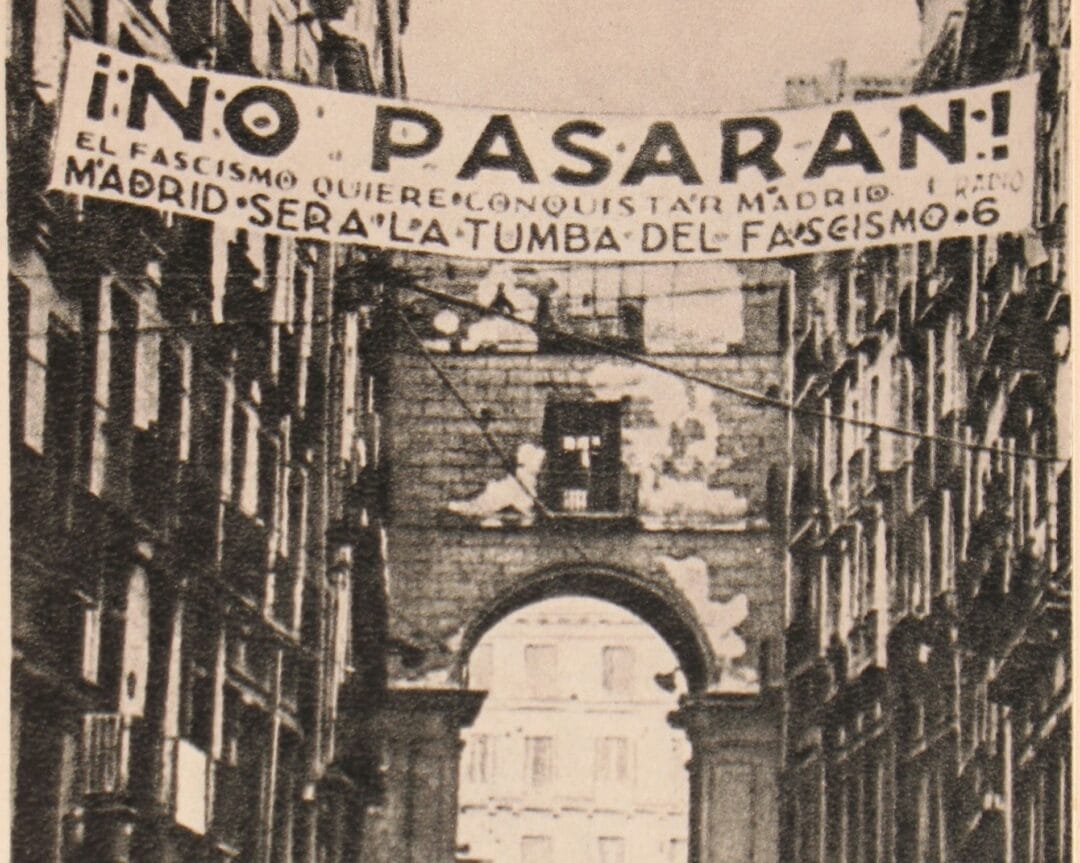

The nationalists launched their attack on the 8th of November 1936 and by the 19th had fought their way through the Casa de Campo, across the Manzanares River and into Ciudad Universitaria. These troops – many of whom were from Franco’s North African army – were well-trained and vicious, however, despite being badly armed, the Republicans fought back just as hard, the city’s citizens cheering them on with the rallying cry of “No Pasaran” (They shall not pass).

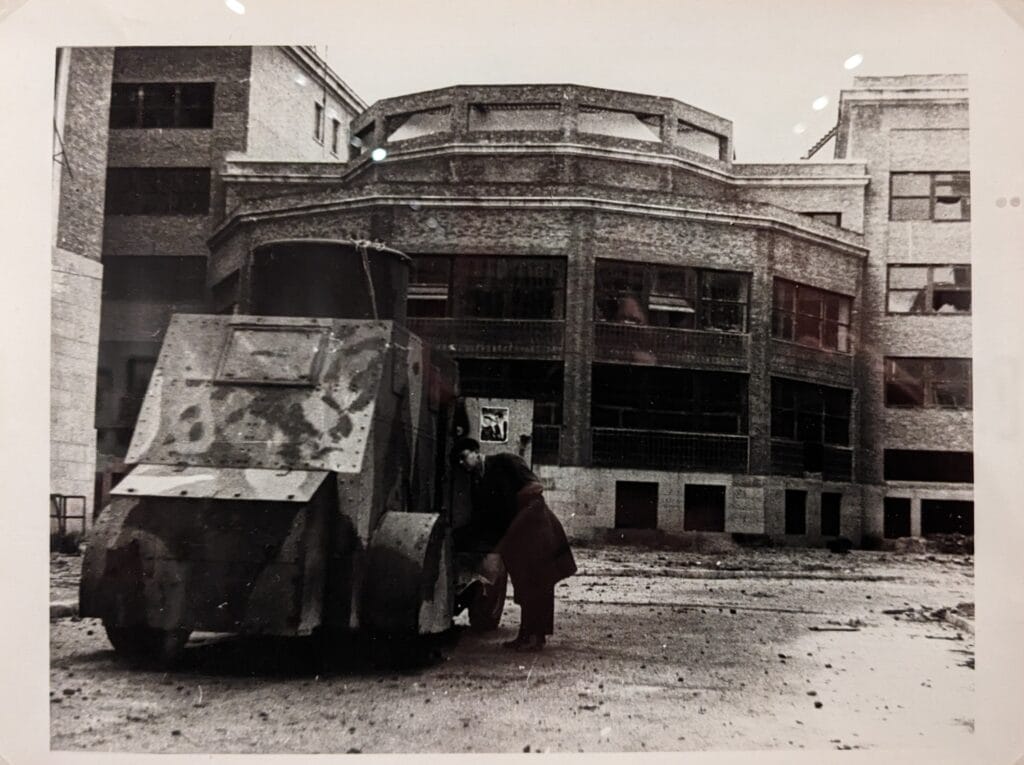

The ground assault culminated in a fierce battle that raged in November of 1936 in University City. Bolstered by the presence of the International Brigades, armed trade unionists, and communists, the ill-equipped Republicans fought tooth and nail taking the fight faculty to faculty using anything that came to hand. According to International Brigade member John Sommerfield, tomes on Hindu metaphysics and German philosophy were particularly useful being “totally bulletproof.”

But behind the bravado was a real fear. Even the dauntless photojournalist Robert Capa, who was there to document the battle, soiled his pants at one point. This was a life-or-death situation; those loyal to the cause fully expected to be executed if the nationalists broke into the city.

Stalemate

The fight ended in a stalemate with Franco digging his troops in for the rest of the war and sanctioning an aerial bombardment of the city by a German airforce eager to test-run new technology. Despite this onslaught, the populace of the city carried on the best they could, dodging artillery fire coming from Casa de Campo as well as the German air raids.

Visible scars at Complutense University

When I went to visit the university on a Saturday, the campus was eerily quiet making it easy to imagine how tense it must have been during the subsequent standoff where troops from both sides occupied different parts of the campus. Madrid would endure two more uneasy years with the nationalists poised to invade right there on the edge of the city. To this day the stone facades of the university’s original buildings remain riddled with bullet holes in an enduring testament to just how hard the Republicans fought to keep the rebels out.

The Civil War in fiction

Though it was my first visit, this area was familiar to me from fiction. Antonio Muñoz Molina’s recent novel In the Night of Time tells the story of a fictional architect who’s putting the finishing touches to this newly built campus just as the Civil War breaks out. It’s an astonishing novel, one of a growing number that are breaking Spain’s long silence on the topic of the war. The hero Ignacio Abel is an architect, caught between two worlds. From humble origins, he has nevertheless gained entry into the ranks of the bourgeoisie. Though he supports the Republican cause, he is made to feel increasingly uncomfortable as the influence of the Communists grows and accusations of class betrayal start to fly.

The university is a sanctuary for him, a monument to ideals he holds dear – to education and progress – making its fate all the more poignant. Ignacio’s own story is just as tragic. He finds himself forced to flee his own country, leaving behind his family, and has to live with the subsequent guilt. Molina provides us with an eloquent account of the dilemma many Spanish intellectuals and artists were faced with at the time; stay and try to fight against all odds for a better Spain, or flee and save yourself. Many figures decided to do the later robbing Spain of the greatest artists and intellectuals of that generation.

The Virgin gets caught up in the action

From the University’s Hospital Clinica San Carlos it’s a short walk towards the Arco de la Victoria (Victory Arch) and it was along this route that we came across a small shrine to the Virgin. A garrulous lady tending an enormous floral display there informed us that this statue was all that was left behind of a church that had once stood on that spot. The bombardment had been so fierce that even Mary herself had not come out unscathed, having had her nose shot off by soldiers during the fighting. Now the Virgin is a symbol of healing in the neighbourhood. Right next to the hospital, many patients visit the statue to pray. Apparently, even non-believers have been known to be miraculously cured after a visit.

Bidding the Virgin’s custodian goodbye, we walked on to the controversial Arco de la Victoria (Victory Arch), a monument constructed to commemorate Franco’s victory; the moment when he finally swaggered into the city and declared “Hemos pasado” (We have passed). These days it’s not looking all that triumphant with the broken steps leading up to it covered in shattered glass.

A troubling monument

It’s difficult to know what to do with a monument that celebrates such an ignominious moment in history, but our mayor Manuela Carmena proposed earlier this year that the arch be renamed the Arco de la Memoria (Arch of Remembrance), not only that but she’d like to turn the structure itself into Civil War museum. Ironically, the arch is hollow allowing for the installation of two lifts that would take visitors up into an exhibition space above.

From the arch we carried on to our final stop; the gun turrets constructed by Franco’s troops in the Parque Oeste. We had a bit of a job locating them in the peaceful park, so for those of you who’d like to go take a peek, here’s the google maps link. The three concrete turrets have a sinister hooded aspect and yet the spot itself is a tranquil one.

Scratching the surface

Nearby us that day were a group of teenagers staging a play battle armed with cardboard swords and scythes. The gentle thwacks of their weapons combined with the birdsong and sunlight trickling down from the pine trees above created the temporary illusion that modern Spain had arrived at a peaceful epoch free from the divisiveness of its recent history. That impression was broken when we arrived in Moncloa Station where many people were waving Spanish flags in protest to Catalunya’s efforts to break away from Spain.

Indeed, central Madrid that day was far from tranquil with thousands of flag-wavingng nationalists calling for the imprisonment of Catalan leaders attempting to declare independence. knee-jerkrk reaction, which, in my opinion, fails to take into account the complexity of the situation. Many in Catalunya feel that the Spanish government has never properly acknowledged the severe repression their culture went through under Franco’s rule. A repression that included the banning of their own native language in public places. In other demonstrations people wore white and chanted the slogan “Hablamos” (Let’s talk). In my opinion, these demonstrators are on the right track; the Spanish need to start talking openly about the past in order to prevent an escalation of the violence we saw in polling stations during the illegal referendum last week. To move forward it’s essential that the Spanish government recognise the psychological scars left by oppression.

Photos by Sergio de Isidro

Wow, this has been a very long post, but I still feel I’ve barely scratched the surface of a very complex subject. For a blow by blow account of how the battle for Madrid went down, I highly recommend this video by the Exploration.

Keen to find out more about the history of Madrid? See another side of the city with one of my unique walking tours.

Pingback: Ground Cerro - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Madrid's Colonias: From Social Housing to Hot Property - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Madrid's Secret Civil War Bunker - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Campeonas: Madrid's female heroes - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: A brief crawl around Madrid's most historic bars - The Making of Madrid