Male narratives have long dominated Madrid’s literary scene. So it was a heartening sight when Almudena Grandes’ name went up in lights in Atocha Station’s tropical garden in March last year. With the station officially rechristened Atocha Almudena Grandes in honour of the recently deceased novelist, it feels as if women’s literature is finally on an equal footing after centuries of repression.

Of course, there have been many other female Spanish authors who equally deserve to be honoured but whose voices have been smothered or forgotten over the ages. When I was commissioned to write a book about the history of Madrid’s literary quarter, I felt that I had a duty to these forgotten voices. Happily, my research turned up an exciting array of talented Madrileñas. To celebrate the launch of my Voicemap Audio Guide to Madrid’s Literary District, I’ve written a little profile of five of my favourites.

María de Zayas

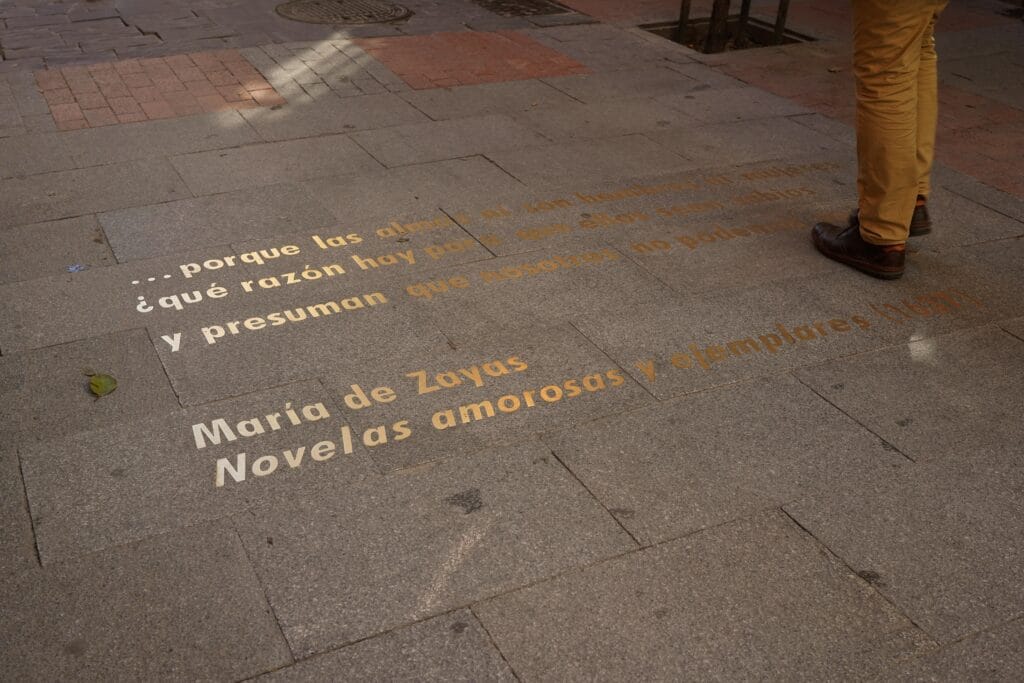

One of the 16 bronze quotes by famous Spanish writers along Calle Huertas in Barrio de las Letras is by María de Zayas. It reads:

Souls are neither male nor female,

what reason is there for men to be considered wise

and women presumed not to be?

Almas ni son hombres ni mujeres,

¿que razón hay para que ellos sean sabios

y presuman que nosotras no podemos serlo?

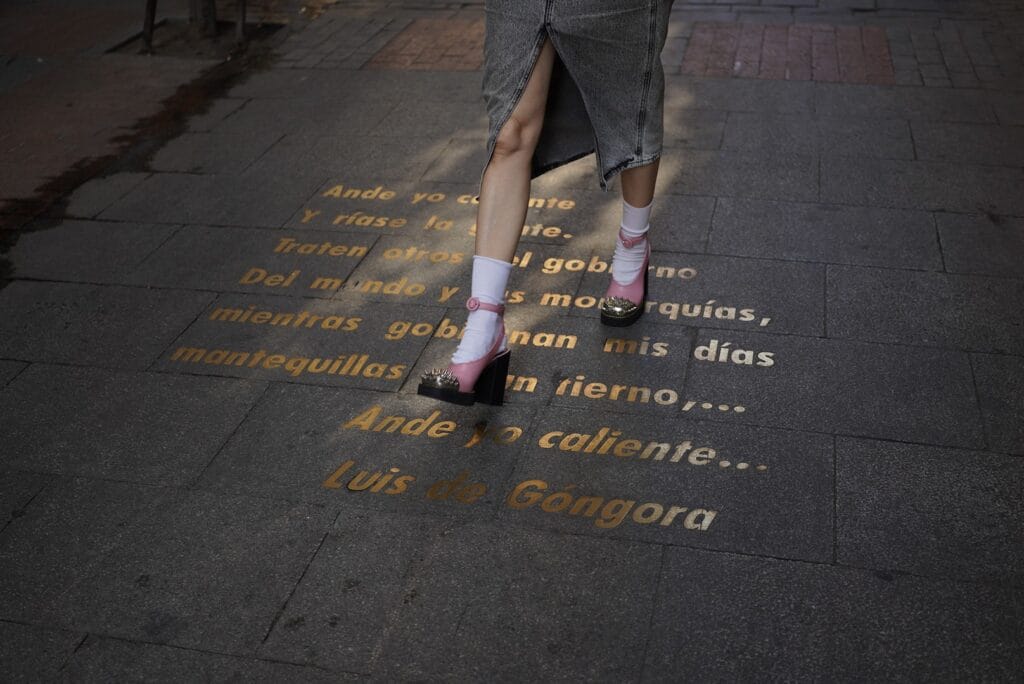

Along with Cervantes and Quevedo, Zayas was one of the most popular writers in 17th-century Madrid. However, her name didn’t appear on the street until 2019. Up until then, only quotes from male writers were embedded in the pavement. It took fierce lobbying by the feminist group Órbita Diversa to get her added alongside two other women.

Admired by Lope de Vega and the second most popular female author in her day after Saint Teresa of Ávila, Zayas was a huge success in 17th-century Spain. Her most famous work is a pair of novels: The Enchantments of Love and The Disenchantments of Love. These are cautionary tales for women told by female narrators. Similar in structure to The Arabian Nights, they are mostly about the various ways men seduce and mistreat women.

One of the reasons she later fell out of literary favour is because she wrote about issues that were generally swept under the carpet. The first story told in The Disenchantments of Love, for instance, details a brutal rape. During this scene, the heroine laments:

“Alas for the feminine weakness of women, made cowards from infancy with all their natural strength dissipated by teaching them how to do hemstitching rather than to handle weapons!”

“¡Ah flaqueza femenil de las mujeres, acobardadas desde la infancia y aviltadas las fuerzas con enseñarlas primero a hacer vainicas que a jugar las armas!”

Emila Pardo Bazán

One of Maria de Zayas’ biggest champions was Emila Pardo Bazán. While the 19th-century novelist was unsuccessful in her attempt to revive interest in Zayas’ work, she did manage to advocate for social equality in her time. Now the two writers keep each other company alongside Rosalía de Castro on Calle Huertas. Bazán’s quote reads:

“To live is to have opinions, duties, aspirations, ideas…”

“Vivir es tener opiniones, deberes, aspiraciones, ideas…”

By her own standards, the novelist lived life to the full. In 1883 she caused quite a stir when La Cuestión Palpitante (The Burning Question) was published. The book passionately supported novelists like Émile Zola and Benito Perez Galdós in their mission to shine a light on contemporary social problems. But her views were too modern for many to swallow and the collection of essays made her persona non grata in some areas of Spanish society.

This prompted her husband to give her an ultimatum: she must choose between marriage or literature. A no-brainer for Bazán, she continued publishing novels throughout her life.

One of Bazán’s triumphs was La Tribuna. In it she describes the tribulations of a cigarrera, that is a young woman working in a cigarette factory. Enduring tough conditions, cigarreras were becoming unionised and radicalised. Like Bazán, many of them were fighting for rights in a country that had long oppressed women.

Though Bazán hadn’t suffered the financial tribulations of her heroine, when she split from her husband, she managed to gain independence through her writing. A pioneer in many ways, she was the first woman to become a member of the Ateneo de Madrid and even managed to rise to the position of head of literature in the male-dominated institution. Bazán’s portrait now sits with Almudena Grandes’ in Ateneo’s gallery of illustrious members.

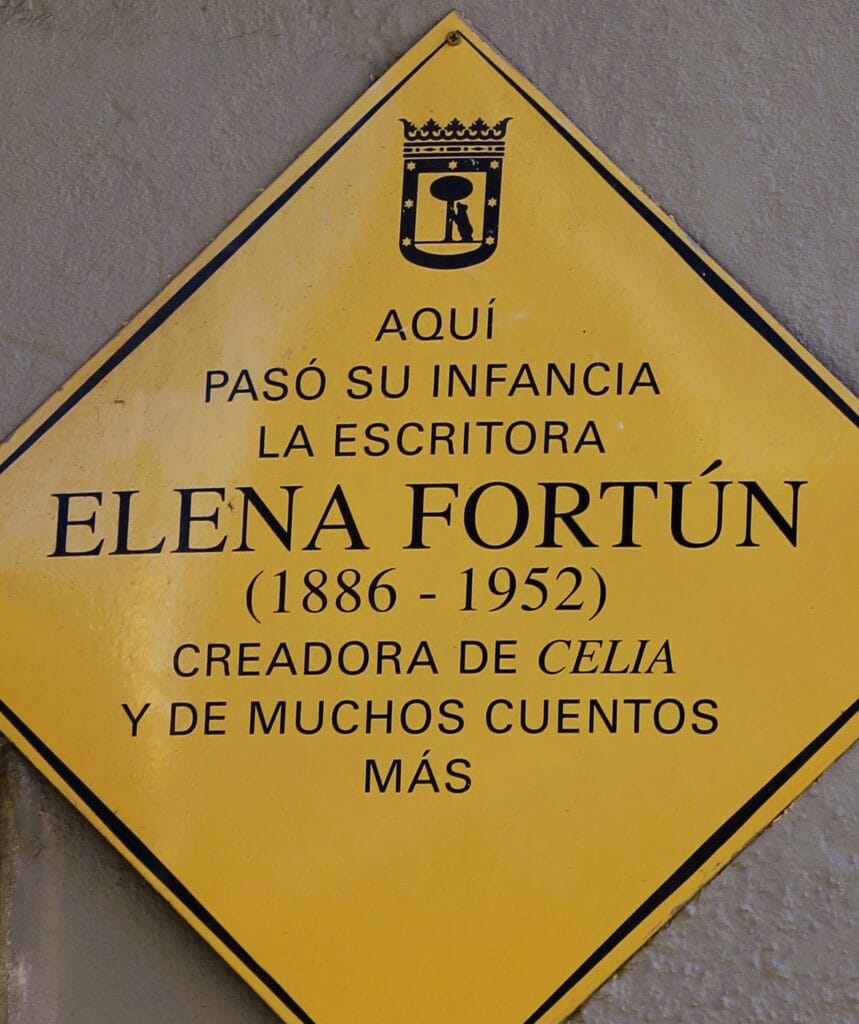

Elena Fortún

At number 41, Calle de Huertas, there’s a plaque to a female author who lived on the street and was beloved by the nation for her children’s stories. More recently, she has become a feminist sensation. Born in 1886, Encarnación Aragoneses took the pseudonym of Elena Fortún when she began writing stories about a naughty little girl called Celia in the years running up to Spain’s Civil War.

On the surface, Elena was entirely respectable. However, her marriage to her second cousin Eusebio de Gorbea Lemmi was almost certainly one of convenience. In fact, she was a member of Madrid’s Sapphic Circle and her correspondence with Quijote scholar and writer Matilde Ras – with whom it’s thought she had a passionate affair – was, along with their collected diaries and essays, published posthumously in 2015. In this video (at 1:30), Almudena Grandes discusses the influence these two women had on feminist thought in their day.

Fortún’s husband was forced to leave Spain after the Civil War and she relocated to Buenos Aires with him where a sympathetic Jorge Luis Borges got her a job as a librarian. There, she worked on Celia en la Revolución, a harrowing account of Celia’s life in Madrid during the long siege of the city. The book was altogether too controversial for its time and wasn’t published until 2020. Her autobiographical novel, Oculto Sendero (Hidden Path), was also published posthumously (in 2016). In this latter work, she openly discusses lesbian desire as well as the difficulties women face in an overwhelmingly male-dominated society.

Gloria Fuertes

If Fortún had stayed in Spain, she might have struggled even more. Under Franco’s regime, homosexuality was illegal. Those found guilty were either imprisoned or sent to mental institutions where electric shock therapy was administered as a “cure”. As women were not generally considered to have strong sexual desires, lesbians like the poet Gloria Fuertes often passed under the radar.

Living just a few streets away from Barrio de las Letras, at 17 Calle Espada, Fuertes was a tenacious talent who refused to compromise. Aged just 21 at the end of the Civil War, the poet and children’s writer spent much of her life struggling financially.

She wrote in the poem Nota Biográfica:

“I wanted to go to war, to put an end to it,

but they stopped me halfway.

Then I got an office job,

where I work as if I were a fool

– but God and the bellboy know I’m not.”

“Quise ir a la guerra, para pararla,

pero me detuvieron a mitad del camino.

Luego me salió una oficina,

donde trabajo como si fuera tonta

– pero Dios y el botones saben que no lo soy –.”

She would eventually show them all that she was no fool, later achieving huge fame as a children’s author. In her barrio of Lavapiés the Jardín Vecinal Gloria Fuertes was established in July 2022 in her memory and a plaque also marks her old home in Calle Espada.

Almudena Grandes

Despite having her name in lights in Atocha, a plaque has yet to go up to mark where Grandes lived in Calle Larra, neither has she had any squares named after her. The delay may well be down to her fierce opposition to the pact of silence that followed the Civil War. After she died back in November 2021, the vote to make her hija predelicta (chosen daughter) of the city was strongly contested by Mayor José Luis Martínez-Almeida and members of the far-right party VOX.

“Later they told us we had to forget that to build a democracy it was essential to look forward, to pretend nothing had happened. And by forgetting the bad, we also erased the good.”

Grandes’ career began when she realised her dream of becoming a novelist with the resounding success of Las Edades de Lulú (The Ages of Lulu), a novel that shocked and titillated audiences with its frank exploration of a young woman’s sexuality. Her popularity persisted as she brought out books, such as Los Besos en el Pan, that introduced readers to characters they could easily sympathise with: ordinary working people, struggling under the weight of Spain’s 2008 financial crisis.

Her historical novels about the Civil War were perhaps her most serious political work. Sadly, she died before being able to complete the sixth and last in the series. The incendiary effect of Episodes of an Endless War is probably one of the reasons why local politicians like Almeida and Ayuso are so reluctant to honour her. Both politicians refused to attend the ceremony to unveil the monument to her in Atocha, turning their backs on one of the city’s biggest literary talents.

Want to know more about Madrid’s Literary District, Barrio de las Letras? Then check out my Voicemap tour of the area or for a deeper dive, buy the book!

Pingback: Literary Madrid: Barrio de las Letras and The Madrid Review - The Making of Madrid