This August, Spain’s women’s team won a huge victory, not just in the realm of football but over sexist machismo attitudes in sport. To celebrate, I wanted to take a moment to honor the brave women in Madrid’s history who stood up for themselves during tumultuous times.

Give it up for Madrid’s female heroes!

The women of Dos de Mayo

On May 2, 1808, Madrid was occupied by Napoleon’s troops. While Spanish soldiers sat in their barracks under strict orders not to oppose the French army, ordinary citizens rose up to fight the occupying forces with pretty much anything that came to hand: pitchforks, flower pots, scissors… This last weapon is said to have been wielded by Manuela Malasaña, a seamstress who was killed by French troops during the fray. Whether she intended to use them or was simply an innocent victim is unclear, but it’s certainly true that the women of Madrid did fight alongside the men.

Two notable names stand out from this battle: Clara del Rey and Benita Pastrana. Clara, who was 47 at the time, fought tooth and nail alongside her husband and three sons, while 17-year-old Benita donned the uniform of her soldier boyfriend (who along with other troops defied orders to stand down). Both were killed. All in all 59 women lost their lives either during the conflict or the reprisals the next day. Their lives were not lost in vain as the event sparked the Peninsula War that eventually freed Spain from French rule.

Concepción Arenal

After the Peninsula War, Spain fell under the totalitarian rule of Fernando VII. The father of our next hero was imprisoned for opposing this oppressive regime. But his rebellious spirit lived on in his daughter Concepción Arenal (1820-1893), who, following in his footsteps, decided to become a law student. The only problem: women weren’t permitted to study law. Undaunted, Concepción began to attend lectures at the law school at Madrid’s Complutense University disguised as a man. When she was found out, the dean of the university insisted she take a test, which she passed with flying colors.

Arenal was permitted to continue sitting in on lectures and also attended intellectual tertulias always in drag. After she married, she began to write plays and poetry. When her newspaper editor husband fell ill, she wrote articles under his name. While she continued to publish after his death under her own name, she was paid much less for her work. Her real triumph, however, was when she was appointed inspector of prisons in Galicia sparking a lifelong fight to reform the system. Many credit her with reforms instituted in the late 19th century.

The cigarreras

The figure of the cigarrera became well known throughout Europe after the success of Bizet’s Carmen. However, this opera painted a romanticized portrait of the women working in cigarette factories. A much more accurate portrayal of them appeared in the 1883 novel La Tribuna by Emilia Pardo Bazán. The feminist novelist spent time in cigarette factories where women were unionizing and beginning to fight for their rights. Madrid’s cigarreras worked in the tobacco factory Tabacalera in Lavapiés and were famed throughout the city for their saucy chulo attitude and militant politics.

Dolores Ibárruri

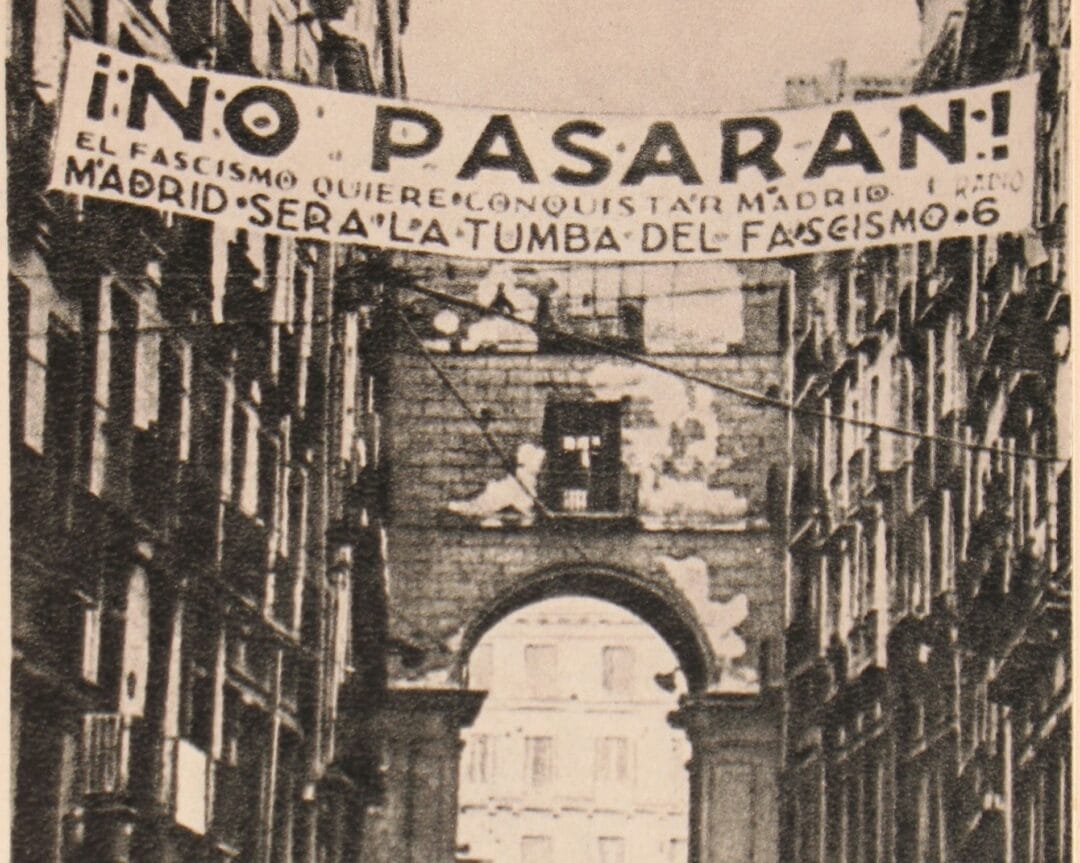

One voice in particular embodied the defiant spirit of Madrileños during Franco’s long siege of the city. As citizens cowered for cover in their homes and beleaguered troops sat in their trenches, the rallying call of Dolores Ibárruri rang out over the radio: No pasaran! Insistent that “they shall not pass” the powerful orator helped keep morale up with lines like: “It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees” and “Madrid will be the tomb of fascism.”

Madrid was, of course, the tomb of Republicanism, and Ibárruri, a Communist, was forced to flee to Russia after the city fell. It wasn’t until May 13, 1977, 18 months after Franco’s death that she was able to return. Sadly her return was presaged by more bloodshed as the Communist party was only legalized in Spain in the fallout from the Atocha massacre.

Almudena Grandes

You may not be aware of this but Atocha Station is now officially called: Madrid – Puerta de Atocha – Almudena Grandes. This rather unwieldy name change is to celebrate the fact that the novelist has been posthumously named Madrid’s first-ever hija predelicta: favored daughter of the city – an honor that has previously only gone to men. While Spain’s far-right party Vox tried to block this appointment from going through, the motion won a majority.

What had got the far-right’s knickers in a twist was Grandes’ refusal to comply with the pact of silence following the transition to democracy. In an article for the New York Times, she wrote: “Later they told us we had to forget that to build a democracy it was essential to look forward, to pretend nothing had happened. And by forgetting the bad, we also erased the good.”

Besides chronicling the lives of Madrid’s citizens in works like Los Besos en el Pan, Grandes also controversially explored the wounds of the Civil War in Episodios Nacionales, a series of novels she was unable to complete before her death from cancer during the pandemic. Despite this small setback, I feel the prolific novelist more than deserves a place in my pantheon of Madrid’s female heroes.

Want to view Madrid from a different perspective? Why not book a tour with me? As a journalist and Lonely Planet guidebook writer, I’ve got a wealth of information at my fingertips. Get in touch to arrange a private tour.