An enduring enigma

Marooned in the center of the Iberian peninsula atop the Meseta Central, landlocked Madrid suffers boiling summers and, in the days before climate change, extremely harsh winters. Regardless, Felipe II decided to settle the court permanently here in 1561. A puzzling move that he never properly explained. Despite leaving behind reams of paperwork, the king didn’t reveal why he chose a sleepy town of 20,000 inhabitants over better-established cities. Nearly 500 years later, the conundrum remains uncracked, an enigma that’s nevertheless a lot of fun to puzzle over.

A central hub

The most plausible explanation might be its central location. Madrid sits right in the heart of the Iberian Peninsula, making it an ideal place to govern from. But if this was the case, why not choose nearby Toledo? In medieval times, the former Visigoth capital was a much larger settlement. One possible reason was that Felipe might have been trying to distance himself from the political power of the church. Though extremely devout and serious about his mission to fight the spread of heresy, he preferred to rule without any outside interference. The church hit back, blocking attempts to establish a separate diocese in Madrid until as late as 1885 – a bizarre standoff that left the capital without a cathedral until 1993.

Another practical consideration was the fact that Toledo’s fast-growing population required a more abundant water source than the Tagus River. Madrid, by contrast, was originally built on underground streams, which were harnessed by its Muslim rulers to irrigate the citadel and surrounding fields. When Christians invaded, they kept Mudéjar hydro engineers on to maintain these systems. The first part of the 12th-century motto of Madrid even refers to this rich resource: “Fui sobre agua edificada” (I was built on water). Madrid is still rich in groundwater to this day though most of the streams that used to run through the city have been incorporated into the underground sewage system.

Bread basket

Building on Roman technology, the irrigation systems installed during the time of Al-Andaluz fed sophisticated water mills that produced large amounts of grain. While Toledo had the windmills of Castilla la Mancha – famously immortalized in Don Quijote – Madrid drew its food supply from surrounding mills fed by the Tajo and Jarrama rivers. Optimized by these hydro engineers to run year-round, unlike windmills, they weren’t dependent on weather conditions and could produce a steady supply of flour to feed the capital’s ovens. One of these water mills still survives and can be visited in Morata de Tajuña, while in the fields near San Martín de la Vega these irrigation systems are still in use!

Structural issues

But water and bread alone do not make a city and when Felipe arrived in Madrid with his entire court in tow, he faced a major problem: a lack of infrastructure. The town didn’t have enough space to accommodate the huge retinue of clerics, officials, nobility, and other hangers-on. To solve this problem, Felipe issued a decree known as the Regalía de Aposento, which forced people to give up parts of their houses to courtiers.

This led to the development of the Casas a la Malicia: trick houses designed to give the impression that they were smaller than they appeared from the outside. These quirky dwellings had sloping roofs, strangely placed windows, and even windows in interior patios that couldn’t be seen from the outside. At one point, there were around 1,000 of these houses in Madrid.

Disconnection

Another huge drawback of Felipe’s decision was that it didn’t make much sense in terms of maintaining communication with his vast empire. As a micro-manager, Felipe wanted to be consulted about all major decisions, but his constant involvement could slow things down considerably. The roads in Spain were pretty poor at the time, and some think that long delays as letters were ferried from Madrid to the ports and onto Felipe’s commanders contributed to the failure of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

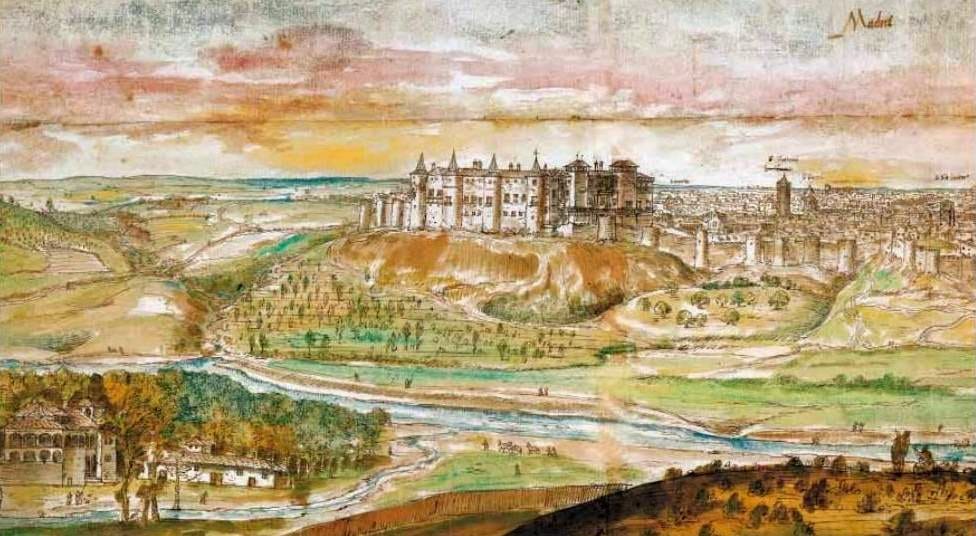

A formidable foe, the well-educated, cautious Felipe was nonetheless a rather private, solitary man who preferred to communicate by letter from his palace in the mountains outside Madrid. A tendency to stay secluded that led some foreign critics to dub him the “spider of El Escorial”. However, he wasn’t entirely serious. When he wasn’t in El Escorial he used Madrid’s Muslim-built Alcazar as his palace and enjoyed hunting in Casa de Campo and El Pardo. Happily, this part of his legacy remains as these swatches of green still cut right into the city.

The icing on the cake

It wasn’t until the 18th century, under the reign of Carlos III, that Madrid began to modernize. A benevolent dictator, the king worked with a group of capable advisors to radically improve the city’s sewage system, street lighting, and rubbish collection. He also commissioned some of the city’s most iconic sights, including the Puerta del Alcala, the Paseo del Prado, the Botanical Gardens, and the building that would become the Prado.

It could be argued while Felipe chose the location, Carlos’ improvements were the key to making Madrid a proper capital. Personally, I wouldn’t have it any other way. Sure, my home city may be smaller than many of its European counterparts, but it’s way cozier and more intimate, while also boasting top-class museums, elegant squares, and vast swathes of inner-city green spaces.

Want to get to know Madrid better? Why not book yourself in for a guided tour? The creator of this blog, I’m also the author of the Madrid chapters for Lonely Planet’s upcoming Spain guides and am a mine of information about the city. Get in touch for more information.

Pingback: Summer in Madrid: “estar de Rodríguez” - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Quiet corners of the Prado - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: Key Moments in Madrid's History: For Whom the Bell Tolls - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: The Hapsburg Jaw - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: The Bear and the Strawberry Tree - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: The Habsburg Jaw - The Making of Madrid

Very interesting! I visited Madrid this past October on my way to do the Camino. A very underrated city in an underrated country.

I hope you enjoyed the Camino. Everyone tells me it’s a wonderful experience.