Europe’s largest shanty town

Most of us associate shanty towns with poorer cities outside of Europe – areas where those below the poverty line live cheek to jowl in substandard housing, struggling to get by without proper access to basic amenities like running water and electricity. With these preconceptions in my own mind, it was quite a shock to discover that Madrid itself is home to Europe’s largest shanty town, parts of which are considered to be so dangerous that even the police fear to enter.

Tucked away in the south-west by the M50 motorway, Cañada Real is a long stretch of land running from La Rioja to Ciudad Real that is home to some 40,000 residents. The neighbourhood is a hangover from the post Civil War era when slum housing was common in the city center and while the last shanty town in central Madrid was cleared in 1994 with the destruction of substandard housing in San Blas, local authorities never got round to sorting Cañada Real out. Indeed, according to El Pais, some migrated there when they were left homeless after being kicked out of San Blas.

Hard to handle

The El Pais article goes on to explain that the problem lies in a tangle of legal issues surrounding the houses in this zone, making it a slippery subject for politicians to handle; built on government land, some are entirely legal, while others quite the opposite. While the buck is being passed around, the residents in some areas have had to fend for themselves sorting out their own electricity and water supplies, despite the fact that they pay taxes that entitle them to such basic amenities.

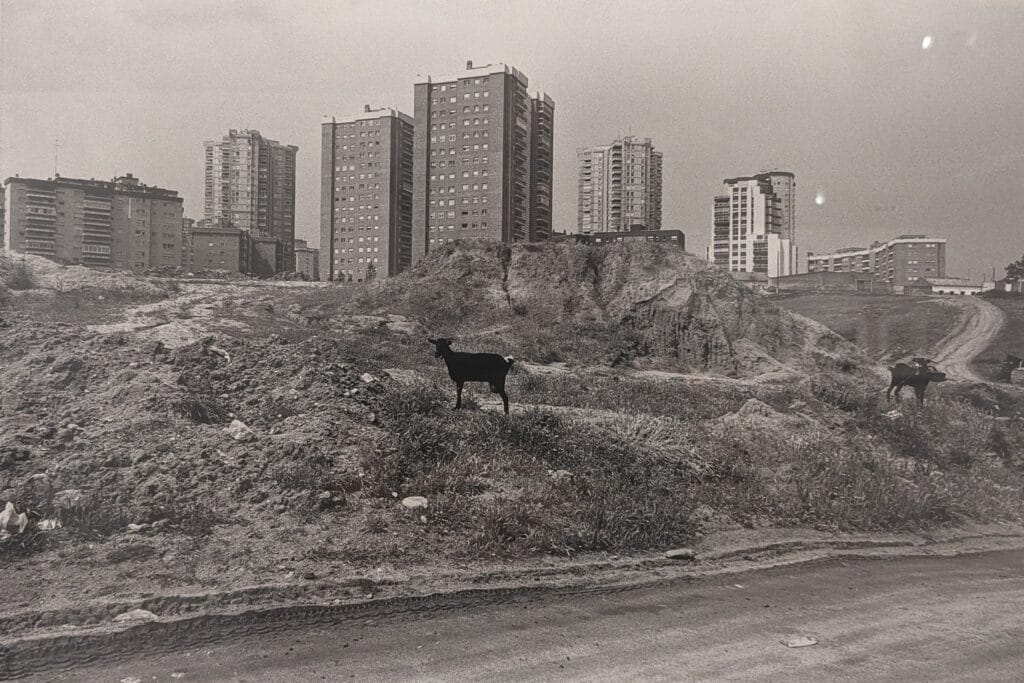

The current population is made up of a diverse mix of Spaniards, gypsies, Romanians, Bulgarians, Moroccans, and Ecuadorians. Many are economic migrants to the country and some don’t have the proper papers to live in Spain. Inevitably, crime is rife in parts, most particularly in the notorious district of Valdemingómez, where the drug trade is so open that junkies score and shoot up in plain sight. However, it’s important not to tar the entire population of Cañada Real with the same brush; according to El Pais, other parts are entirely respectable (see photo below).

The issue of regulating illegal housing has dogged the city since its population exploded at the end of the Civil War. In the poverty-stricken era between 1940 and the 1960s, economic migrants flooded into Madrid from the Spanish countryside, most particularly from the areas of Andalusia and Extramadura. Between 1940 and 1950, 366,000 new residents arrived from rural areas and in the subsequent decade another 392,000 or so arrived. Many of them were unable to find housing, so were left with no other option but to construct their own. The issue got so bad that in 1957 the government declared that new arrivals who couldn’t prove a place of residence were to be ejected from the city. In the same year the systematic demolition of slums began. One such slum was Jaime el Conquistador located in the area now known as Legazpi. According to Urban Idade – an excellent blog about the history of urban development in Spain – when this shanty town was finally demolished in 1957, the residents were transported to newly-built housing in San Fermin.

Urban clearances

After this initial wave of clearances, the police began to patrol what was then the outskirts of Madrid in an attempt to catch people in the act of putting up houses. I live in Almendrales, which is just across the river south of Legazpi. In the years following the war, many migrants bought parcels of farming land here and erected shacks without any planning permission. In order to dodge the patrols, the whole neighbourhood would get together to put a house up overnight thus presenting the authorities with a fait accompli. Though some of these bungalows were charmingly rustic, they weren’t the most comfortable places to live in, having no running water or electricity. When these houses were finally bulldozed they were replaced with brick apartment blocks similar to the ones in nearby San Fermin. I live in just such a block in an area that despite its rough reputation is, with its first-wave population of staunch elderly Spaniards and second-wave of immigrant South American families, a rather a nice place to live.

Pockets of slum housing remained in central Madrid right into the 80s, attracting a criminal population that was able to operate unmolested by the police. Back in the day if you wanted to score drugs you simply had to pay a visit to El Salobral in Villaverde, Pitis in Fuencarral, and La Celsa in Vallecas. Now with these gone, Valdemingómez in the aforementioned Cañada Real has become the place to score. There´s even an unofficial junkie bus service that leaves from outside Embajadores station to take addicts to this notorious area. A scruffy friend of mine realised he might have to smarten up his act recently when a driver approached him outside the metro and offered to take him there for a few euros!

Out of mind

Having these areas remain out of sight means that little pressure is being put on politicians to sort the problem out, however, though the wheels of local government turn slowly, there are schemes in motion to improve the lot of Madrid’s most deprived populations. Close to Cañada Real is Gallinero, a Romanian gypsy settlement that is home to around 450 inhabitants, 300 of whom are minors. According to Vice, the area is quite literally a dump with rubbish reaching up to the ceilings of some structures. Crime is the only source of income available to many and some eek out a living stealing and selling on copper wiring.

If the Ayuntamiento gets its way, the whole place will be destroyed and the families moved on, either back to Romania or relocated to social housing. However, for now, the dirt road running through the settlement has been temporarily repaved so that a bus can get through to take the children to school and a standpipe has been installed to provide fresh water. But it’s hardly luxurious; a constant traffic of shopping trolleys filled with plastic bottles of water travels up and down the central road of the settlement.

Spain’s gypsy population has long had a fraught relationship with “normal” Spanish people. I’ve certainly witnessed open hostility expressed on both sides. So integration is, understandably difficult to pull off, which is why the people of Gallinero will have to go on socialisation courses when they are eventually rehoused (that is if they aren’t shipped back to Romania). Groups will also be split up to avoid the “formation of ghettos”. In an interview in El Pais, Isabel Pinilla director of the agency for social housing commented that “Afterwards they are kept an eye on to avoid problems with the neighbours.” Pinilla also added that she’d like to put an end to the shanty towns in the next five or ten years. Whether or not that really is possible remains to be seen.

Postscript: I wrote this post inspired by an excellent piece in Madrid No Frills on Vallecas’ transformation from shanty town to thriving multicultural district. It’s a cracking read which I urge you to check out.

Canada Real Galiana is a m-long, -wide strip of economic and social misery. Believed to be Europe’s largest shanty town, it is a mere 15-minute drive from Madrid city centre. “This place reminds me of one of the most run-down slums in Guatemala I used to work in,” says Susana Camacho, who works for Fundacion Secretariado Gitano (FSG), a local NGO.

Pingback: Gangs of Madrid: Is Madrid a Safe City? - The Making of Madrid

Pingback: What is Madrid made of? - The Making of Madrid